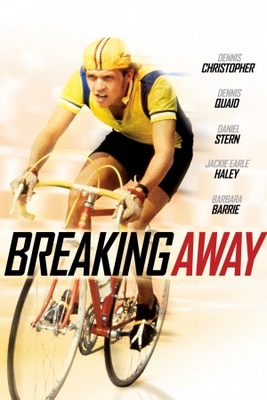

Our next potential classic is a true sleeper hit from 1979, the feel-good bicycle racing film Breaking Away. It seemed to come out of nowhere, making an (albeit brief) star out of Dennis Christopher and launching the careers of his costars Dennis Quaid, Daniel Stern and Jackie Earle Haley, each of whom has eclipsed Christopher’s accomplishments. The film was not just commercially popular but highly acclaimed, earning multiple Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations, and spawned a short-lived television series the following year. It was a genuine phenomenon while it lasted, but more than thirty-five years later it seems to have been largely forgotten. Perhaps our looks at Breaking Away will rekindle some nice memories for some of you.

Our next potential classic is a true sleeper hit from 1979, the feel-good bicycle racing film Breaking Away. It seemed to come out of nowhere, making an (albeit brief) star out of Dennis Christopher and launching the careers of his costars Dennis Quaid, Daniel Stern and Jackie Earle Haley, each of whom has eclipsed Christopher’s accomplishments. The film was not just commercially popular but highly acclaimed, earning multiple Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations, and spawned a short-lived television series the following year. It was a genuine phenomenon while it lasted, but more than thirty-five years later it seems to have been largely forgotten. Perhaps our looks at Breaking Away will rekindle some nice memories for some of you.

The college town of Bloomington, Indiana is the setting, where a quartet of friends faces impending adulthood with trepidation and resentment. Dave (Dennis Christopher) is in the midst of what his parents hope is a phase; he loves everything Italian, and is training to race against the vaunted Italian bicycle racing team when they come to town. Dave is so entranced with the culture that he tries to impress a comely college student, Katherine (Robyn Douglass), by pretending to be an Italian foreign exchange student. His friend Mike (Dennis Quaid) is also athletic, but full of bitterness for not being affluent enough to attend college and play football. As a result Mike is constantly getting into trouble, especially fights, and usually bringing his friends with him.

Moocher (Jackie Earle Haley) loves his pals, but he’s actually got his eyes on getting a job to provide for his girlfriend, whom he tries to keep secret from his buddies. Cyril (Daniel Stern) is just plain goofy. Together they form a close-knit group, the kind that one can say just about anything within without fear . . . and they do. The beauty of Steve Tesich’s Oscar-winning script is that it captures the honesty of sharing life’s crazy experiences with friends. Each of the guys must find his own way, and they do, but most of their experiences are shared with one another before they reach full adulthood and are forced to separate for good.

The other major relationship depicted in the story is that of Dave Stoller to his parents (Paul Dooley and Barbara Barrie). At first it is played strictly for laughs, as Dave drives his father crazy with all the Italian stuff. His mother has far more patience, but even she is perplexed by her son’s odd phase. Later, as the story turns serious, the bond between father and son strengthens and a couple of scenes become very poignant. His dad visits the limestone cutting facility where he used to work before taking a dilapidated used car dealership (the kids are known as cutters because the stone cutting facility employed many of the Bloomington townspeople at one time). For perhaps the first time in his adult life, Dave realizes that his father was actually good at something, and still carries a great deal of pride about it. And because his dad spent years cutting stone he has had a rather comfortable existence.

The other kids’ stories are touched upon but this is Dave’s movie all the way. He has his first adult romance, with the college girl Katherine (Robyn Douglass), but because he isn’t honest with her, it ends badly. He idolizes the Italian racing team, but when they don’t take kindly to his friendliness, he loses his innocence forever. He can feel his youth slipping away and can do nothing about it; he has to become an adult and start to make money to support himself. He knows his friends are going to slip away as well, but before they do there is one last shared experience that they can savor together.

The boys hope to prove to the college kids that they are just as good as they are by beating them in the annual bicycle race, the Little 500. It seems odd that the locals are actually “given” a spot in the race, which makes the college teams angry. A major part of Steve Tesich’s script is the rivalry between the local kids, the “cutters,” and the college kids. Much is made of the fact that the limestone provided by the “cutters” over the past few decades has gone into constructing the hallowed halls of Indiana University, and that now the local kids, and their parents, are unwelcome there. That emphasis, of course, makes the audience root harder for the local boys to ride the snotty college kids into the dust.

Although Breaking Away is not a sports film per se, its latter half is formulated like one. Dave trains hard for the race, which he expects to ride alone, with his lazy teammates cheering him on. But a wreck in the race forces Dave to the sidelines and his friends onto that very uncomfortable seat. It truly becomes a team sport movie then, made even more poignant by Dave’s father leaving his empty used car lot to watch his son do what he loves. It’s tremendously exciting and quite emotional as the bicyclists race to the finish line.

The race is what many people remember most vividly, especially those who ride or race bicycles as Dave does in the film. But others recall the friendship, or the kooky romance (particularly the serenade scene, when Cyril shines his brightest), or the way that Dave finally reconciles with his father. For it is the people who matter. Dave could have been a chess prodigy, or a really good debater, or a hockey champion, and the story would still work because we learn enough about him to care about him and his friends, and their futures.

Besides the beautifully-written characters and the exciting race which climaxes the story, its other real asset is a sense of place. Like Hoosiers and Rudy, both Indiana sports movies which followed Breaking Away by several years, this film is masterful at evoking its midwestern locale. The quarry is a strong recurring highlight, yet director Peter Yates lenses all over the Bloomington area to convey a genuine feel for the area. Location filming almost always improves the mise-en-scène of what is shown on screen, whether the setting is romantic Rome, gritty New York or, in this case, rural / suburban Indiana. While certain places are attractive (the quarry, the campus), the utter monotony of others fuels Dave’s drive to romanticize the Italians and his friends’ hopes of getting away from Bloomington as quickly as possible.

1979 was a year of really, really good movies, and Breaking Away was widely considered one of the best. It was a big hit, launching the film careers of its four young stars and was perhaps the pinnacle for its veteran cast members. Barbara Barrie earned an Oscar nomination as Dave’s mother, and Paul Dooley is still thought to have been snubbed by not receiving his own nomination. The film was nominated for Best Picture, Director, Score and Original Screenplay (it’s only win). It won the Golden Globe for Best Musical or Comedy and was chosen by the National Society of Film Critics as the best film of the year.

Is it a classic? Yes. I am slightly less enamored of it than others, mainly because I don’t care much for the character of Dave. He irritates me. I feel the rest of the film is really good, but Dave is over-written, or perhaps too unique for his own good. I also feel that too much emphasis is given to the climactic race, which changes the tone of the piece from sly Americana to rah-rah celebration. For me the best parts are the seemingly ad-libbed conversations between the four friends, and the solo scenes where Dave is the most tranquil while riding beneath a canopy of trees, or testing himself by chasing a semi-trailer down a long stretch of highway. Breaking Away is a good, solid movie because it has a perceptive, character-driven script. And if it has been largely forgotten, or never seen, by audiences of today, it is certainly worth rediscovering, or seeing for the first time. See it, and then go enjoy a nice bike ride. ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 10 December 2015.