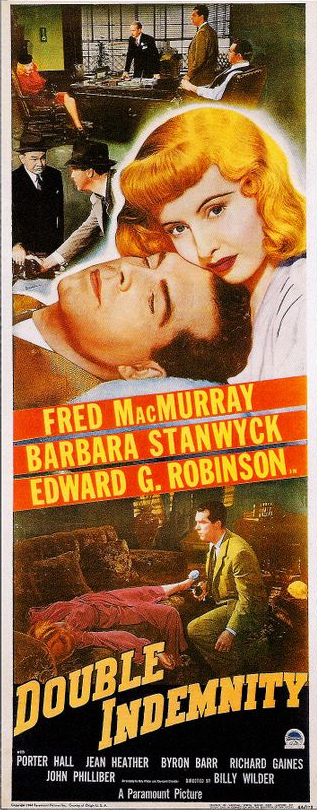

Writer-director Billy Wilder was just reaching his peak in the early 1940s, hitting his first grand slam with this noirish murder mystery. It was so well-received that its two word title, swiped from insurance industry lingo, has become more synonymous with this movie (and James M. Cain’s original novel) than the insurance coverage itself. This movie is among the high points in the careers of everyone associated with it, especially Fred MacMurray, who excels in the “sucker” role — which seems indescribably odd to anyone who grew up watching him as the squarest parent imaginable on “My Three Sons” or a host of Disney comedies. But Wilder knew how to uncover and exploit MacMurray’s darker instincts, which he did here and in The Apartment (1960), providing the affable actor with his two finest roles.

Double Indemnity is a triumph of cinema, conveying its story of lust and greed and murder in almost Biblical proportions. Once the premise is established the story goes into overdrive, with almost no extraneous matter; everything is connected to or threatens the unholy dalliance between unhappy wife Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) and lonely insurance salesman Walter Neff (MacMurray). The story is narrated by Neff, who begins near the end of the tale and then resets the story to expose his fully understandable stupidity. It is a very linear storyline, deflected only by the presence of Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), Neff’s colleague, a claims manager who eventually smells a rat, as these characters used to say back in the day.

Wilder and co-writer Raymond Chandler adapted Cain’s novel and added the crackling dialogue for which the movie is so cherished by film fans. Wilder wanted to add heat to the proceedings, which could only be done through dialogue and staging thanks to the Production Code, and boy did he succeed. The film smolders with latent sexual passion, coded into the dialogue and visually represented by Stanwyck’s appearance, particularly her legs. In the ’40s Barbara Stanwyck had the best legs in Hollywood (see The Lady Eve and Ball of Fire for proof, as well as this film) and in the early scenes Wilder has her pose them as provocatively as possible, along with an anklet that serves as the focal and vocal point, for Neff’s benefit. (Cyd Charisse would claim the best legs crown in the ’50s.) Between the double-edged dialogue and Phyllis’ alluring attractions, it is no surprise that Neff is soon a goner.

The writing is superbly delicate as Phyllis intimates much, attempting to goad Neff into suggesting the murder plot on his own, making it his idea rather than hers. But he knows exactly what is on her mind, and walks away . . . only to realize that he doesn’t want to walk away. It helps that Neff is half-smart, although he believes himself to be much more on the ball; he catches on fast, but never bothers to work it through to the end in his haste to taste the affection Phyllis is offering him. This aspect was wonderfully realized — and parodied — in Lawrence Kasdan’s brilliant homage to this film, 1981’s Body Heat, when Matty Walker (Kathleen Turner) chides Ned Racine (William Hurt) in this way: “You’re not too smart, are you? I like that in a man.” No such parody interferes with the smoldering passion in Double Indemnity — although modern audiences may not appreciate the subtle charm of Neff’s narration: “How could I have known that murder could sometimes smell like honeysuckle?”

Two relationships revolve around each other like binary stars in this film, finally colliding in the final minutes, when Neff concludes his tryst with Phyllis, and when he confronts Keyes in his office. Neff’s sexual attraction to Phyllis is primal and urgent, but it is rarely romantic; indeed, Neff tells Keyes that he loves him, twice. The dark side of Neff’s nature is exploited by Phyllis, who wants as much as she can get out of this life, no matter what the cost to others. But Neff’s relationship to Keyes is on a higher plane. They are colleagues, sharing their intellects and instincts about business and life. Keyes wants Neff as his assistant, a position that Neff wants no part of — I think, because he enjoys exploring his dark nature and he knows that he could never get away with that working so closely with Keyes. Indeed, while the physical pleasures provided by Phyllis are powerful, it seems to me that Neff derives another type of thrill by deceiving his friend and mentor at work. It is the only time that he can “better” his colleague, at least until events take their inevitable course, as Neff knows they will. Of course he wants to get away with the crime, but on some level, Neff hopes that it will be his friend who solves the mystery and comes for him.

The real power of the film lies in Wilder’s (and Cain’s) insistence that turning to crime — even murder — takes so little effort. Neff is just a regular guy with a good job, one on the right side of the law, yet all it takes to push him over the brink is a nice pair of legs, whispered endearments, a sense of chivalry and the promise of further excitement. He moves from boor to adulterer to murderer in quick steps, manipulated by a cold-blooded dame who knows exactly how to pull his strings. Phyllis’ amoral character, however spectacular, is mostly one-dimensional, but Neff’s descent is a study in the psychology of the dark side of human nature. Especially near the end, when Neff takes the final step with Phyllis. That mild-mannered insurance salesman Walter Neff can be so easily lured into killing someone else is the real story here, supplied by James M. Cain, and turned into art by Billy Wilder.

Two supporting characters are important: Phyllis’ step-daughter Lola (Jean Heather) and Lola’s boyfriend Nino Zachetti (Byron Barr). Lola is interesting because her relationship with Phyllis — and her own father — are so strained; the reasons for this come out during the narrative and are quite compelling. She also becomes sort of involved with Neff, who ostensibly takes her out to keep an eye on her and prevent her from spreading stories about Phyllis — but I think his closeness to her also keeps him completely tied into the Dietrichson family dynamic, which is the most exciting situation he has ever experienced. He just cannot leave it alone. I feel differently about Nino Zachetti. I don’t like the character as written or the way he is portrayed by Byron Barr. Nino is eventually set up to be the fall guy, too, yet at the last moment Neff tries to redeem himself by forcing Nino away from Phyllis’ home. I actually would have preferred that Neff let Nino be ensnared in the murder plot; he was a jerk.

The concept and look of film noir was still under construction in 1944; in fact, I don’t think the term had even been invented yet. Double Indemnity went a long way toward defining the genre with its multitude of shuttered windows and horizontal blinds, its shadowy lighting of already dim interiors and its acts of passion and violence done in the dark. It has bright scenes at the insurance offices and the wonderfully designed supermarket, yet even these seem like unsafe places thanks to the deed being planned and discussed at the supermarket (and the dark glasses worn by the protagonists) and the almost warlike plotting and confrontations staged at the insurance offices. It is also interesting that the really good scene in the hallway outside of Neff’s apartment contains an error — the apartment door would open into the apartment, not the hallway (it’s a fire safety rule). But Wilder needed the door to hide Phyllis, so things were changed so it could be staged in that manner.

Sharp-eyed viewers may notice that Neff wears a wedding ring (Barb noticed), but the continuity people didn’t see it until post-production. Neff also makes reference to “The Philadelphia Story,” which didn’t appear on Broadway until 1939 and on film until 1940, although Double Indemnity takes place in 1938. There’s always something a little out of whack for someone to find.

Most everything else works for me. I don’t care for the way that Neff calls Phyllis “Baby” so often, but what can you do? MacMurray also seems rather stiff in some scenes, but I take that as his character “stiffening up” when questions are raised about the Dietrichson case. MacMurray is great at the very end, trying to make it to the elevator; it’s one of the most realistic and convincing portrayals of someone slowly dying that I can recall. Edward G. Robinson is great throughout. He brings kinetic energy, cantankerous personality and genuine intellect to the film, improving it in every way imaginable. And Barbara Stanwyck is superb as the scheming femme fatale. The script tries to give Phyllis a redeeming moment at the end, too, like it does for Zachetti, and it is almost convincing. Enough to make one wonder.

All in all Double Indemnity helped usher in a darker sort of movie entertainment. It reminded audiences that not every character, or familiar actor, is to be trusted. It made murder seem easy — except for the lingering questions of conscience and nerve. It’s also one of the few murder mysteries not to involve police at all; not a cop is to be found. I cannot stand the insurance racket, but it even makes that seem interesting. It established Billy Wilder as an artistic force in Hollywood, and was a monumental success. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards but didn’t win any, losing the top prizes to Going My Way.

Is Double Indemnity a classic? You bet it is! Relatively few films have had the impact and long lasting legacy as this one. It is a bit dated, a product of its time, but its influence has not dimmed in seventy years. It was remade as a made-for-TV movie in 1973, and was essentially remade again in 1981 as Body Heat, which is a film I like even better than this one. The lack of restraints allow Body Heat to portray the lust and passion so central to the story in visceral ways that Double Indemnity could not accomplish. Yet Double Indemnity manages to sneak a few things past the censors and certainly conveys its very adult story in very adult ways. It was produced during the height of World War II, yet even with its dated aspects it sustains a timeless quality which remains quite powerful today. I believe that is because it understands and reveals how fragile civilized behavior can be, and how that can deteriorate into violence and murder with a gentle push. ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆. 23 September 2016.