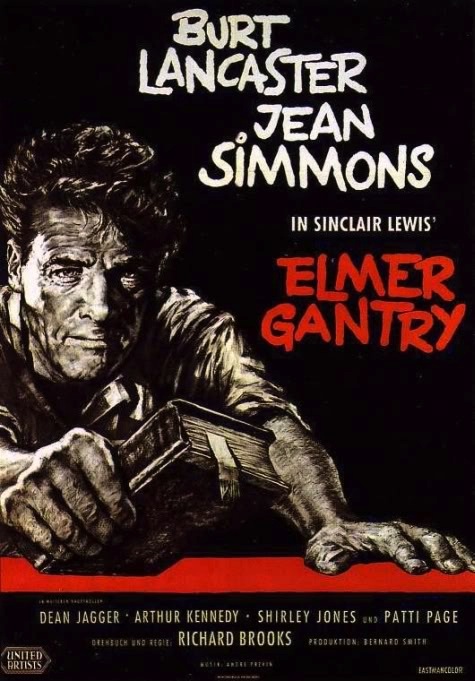

Our second classic of 2014 is Elmer Gantry, a melodrama that takes aim at revivalist religion, based upon a satirical novel by Sinclair Lewis. As adapted by writer-director Richard Brooks this 1960 film becomes a period piece of the late 1920s, using only one hundred or so pages of the novel as its structure and changing the basic character of Elmer Gantry from an ordained minister (and one who switches religions from time to time) to an energetic salesman who happens to a know a great deal about the Bible. By eliminating the book’s intimate connection of Gantry to organized religion and making him an outsider, Brooks deflects much of the book’s inherent controversy (no less than Billy Sunday referred to Lewis as “Satan’s cohort” when the book was first published). Since Gantry is, in the film, a salesman who can pitch religion as well or better than vacuum cleaners, the film isn’t directly exposing, indicting or condemning the establishments of organized religion or even evangelism. Elmer Gantry is merely one example of a huckster who has some success preying upon the cherished beliefs of a gullible populace.

Our second classic of 2014 is Elmer Gantry, a melodrama that takes aim at revivalist religion, based upon a satirical novel by Sinclair Lewis. As adapted by writer-director Richard Brooks this 1960 film becomes a period piece of the late 1920s, using only one hundred or so pages of the novel as its structure and changing the basic character of Elmer Gantry from an ordained minister (and one who switches religions from time to time) to an energetic salesman who happens to a know a great deal about the Bible. By eliminating the book’s intimate connection of Gantry to organized religion and making him an outsider, Brooks deflects much of the book’s inherent controversy (no less than Billy Sunday referred to Lewis as “Satan’s cohort” when the book was first published). Since Gantry is, in the film, a salesman who can pitch religion as well or better than vacuum cleaners, the film isn’t directly exposing, indicting or condemning the establishments of organized religion or even evangelism. Elmer Gantry is merely one example of a huckster who has some success preying upon the cherished beliefs of a gullible populace.

Gantry (portrayed with immense charm and charisma by Burt Lancaster, who won his only Academy Award for the role) is a learned man who was booted out of a seminary for seducing a young woman behind a pulpit, now reduced to making a living as a regional salesman, shilling vacuum cleaners and cheap goods to merchants who cannot sell them. He is surely a believer in God, yet that doesn’t stop him from drinking and telling dirty jokes and womanizing in every city he visits. That is, until he observes Sister Sharon Falconer (Jean Simmons) in action. Her grace and beauty overwhelm him, as does the palpable connection she creates with the audiences who come to hear her evangelize. He is smitten at once, and drops everything in order to persuade her that he can help her deliver God’s message, as long as that will bring him closer to her.

Although Gantry is the title character, Sister Sharon Falconer (Jean Simmons) is really the key figure in this fable. Based on the controversial yet iconic evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, Falconer changes the movie’s course as soon as she appears, her soft angelic features beguiling Gantry in a way that no other woman can. Falconer seems perfectly pure and virtuous, a woman dedicating her life to save the souls of others, and yet Gantry cannot help but be attracted to her like a moth to a flame. It is an attraction that seems doomed because she instantly recognizes him for the huckster that he is — and yet, Gantry persists, knowing that beneath all the altruism and purity there is a woman of flesh and blood. He knows how to seduce women, yet it isn’t until he discovers her secret past that he allows himself to go forward, because it is then that he sees how much like himself she really is. A dramatic scene on the sand beneath the boardwalk seals their fate together.

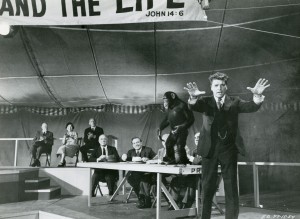

Soon Gantry is a major part of her traveling show, bombastically and energetically delivering the word of the Lord, while she takes a subtler approach. Various viewers have remarked that Burt Lancaster’s innate charisma essentially drowns Jean Simmons’ personality, and so weakens the drama. I disagree, for Lancaster’s entertaining rants and raves regarding fiery hell and damnation are rather common in revival meetings. Simmons’ quiet grace and beatific presence invites trust in a manner that speaks more directly to the heart. Together they make a powerful duo, and the premise suggests that, together, their characters could create a remarkable presence in the evangelism scene. The only question is dedication; Sister Falconer demonstrates her resolve by secretly building her own tabernacle, while Gantry may have lesser goals in mind.

And this is where the movie struggles a bit. It tries to work both ways: satirizing and criticizing the business aspects of religion, while defending the aims and motives of the people selling it. This is an uneven and uncomfortable mix at times. Sister Falconer recognizes the need for money and popularity, though she would rather avoid any aspect of peddling or promotion. Gantry, on the other hand, knows exactly what needs to be done and coerces, shames or blackmails any one who stands in the way. Sister Falconer lives almost entirely for her ministry and despairs when earthly demands intrude upon it. Elmer Gantry understands human affairs and simply adjusts to meet them when need be. And the church officials of mythical Zenith are in between, desirous of bolstering church attendance and revenues and willing to allow the pair of traveling evangelists to stick around for six weeks to build interest and excitement.

Into this hotbed of religious fervor and commerce flounces pretty blonde prostitute Lulu Baines (Shirley Jones, in her Academy Award-winning role). Lulu is the reason that Elmer Gantry had to leave the seminary, and he is the reason her father booted her into the street, having to survive any way that she could. After the police raid the brothel where she is working, she calls Gantry to make amends. He gives her some money and believes that to be the end of it. But hell hath no fury like a hooker arrested, and Lulu has her own agenda. And yet, when she attends the nearly empty revival meeting that takes place after the newspapers print pictures from their meeting, Lulu is shocked to see Gantry publicly shamed, humiliated and attacked. This is where the movie transcends its melodrama. Lulu runs away and Gantry follows, only to save her from being beaten by her pimp. Gantry slaps the man in retaliation (“Don’t you know that hurts?”) and then throws him down the stairs. Gantry gently dabs his handkerchief at her bloodied mouth until Lulu wakes, then softly apologizes to her for everything. It is the movie’s most perfect moment and it redeems him for all the scheming and dealing that he has done before.

One other character bears mention, and that is newspaper columnist Jim Lefferts (Arthur Kennedy). Based on the figure of H. L. Mencken, Lefferts is researching a story on revivalist evangelism and is constantly around Sister Falconer and her traveling troupe. He witnesses everything surrounding her and eventually writes a generally scathing article that condemns her particular brand of revivalist evangelism. And yet he befriends Elmer Gantry and Sharon Falconer because he, unlike so many others, is able to separate his feelings about life from his feelings about people, and he recognizes both of them as good people. Lefferts is the voice of reason in the film, never more so than when he explains why he refused to buy Lulu’s blackmail photos, terming them “pornography and lies.” Lefferts also tries to rescue both Gantry and Falconer at different times, essentially trying to protect them from themselves and what they have wrought.

Lefferts reminded me of another character, that of journalist E. K. Hornbeck, in another 1960 film, Inherit the Wind. As portrayed by Gene Kelly, Hornbeck is a blowhard who moralizes upon everything and holds everything in contempt. The character is a sharp portrayal of H. L. Mencken, who actually covered the real-life “Scopes monkey trial” for his Baltimore paper, so it is no accident that the two characters are similar. Lefferts is much gentler and easygoing than Hornbeck, but they definitely share attitudes and philosophies. Hornbeck really sticks out in Inherit the Wind because Kelly plays him as a heel, whereas Lefferts comes across as a guy with whom one could enjoy a friendly drink. Upon further viewings, it isn’t Elmer Gantry or Sharon Falconer to whom my attention is consistently drawn — it is Jim Lefferts.

One aspect I really like about this film is the dialogue. In his sermons Gantry rails against all sorts of “isms” and happens to mention both Sinclair Lewis and H. L. Mencken as bad influences. When Lefferts hands Gantry a bottle after the riot, the preacher man takes a drink and says, “God, that’s good.” A moment later Lefferts, a dedicated atheist, asks him if he really does believe in the Lord. “Damn right I do,” is the explosive reply. A natural speaker, Gantry has ready lines about love that will lure any woman into bed and yet will also explain the beauty of God’s presence in human hearts. Much of the dialogue is ironic and even laugh out loud funny, such as when Lulu is rejected by Gantry because of his feelings for Sharon Falconer. “The Bible broad?” exclaims an astonished Lulu. Or Gantry’s description of his first visit to Zenith: “I was accosted by three painted women. Your streets are made unsafe by shameless, diseased hussies, rapacious pick-pockets, and insidious opium-smokers.” Or Lulu Bains’ lurid description of her moment of passion with Gantry behind the pulpit, which must be heard to be properly appreciated.

Is Elmer Gantry a classic? To paraphrase the main character’s own words, “Damn right it is.” This is a vivacious, highly entertaining melodrama with some great performances to bolster its appeal. It is certainly a classic, and even at 146 minutes is not overlong. It isn’t as scathingly satirical as Lewis’ book — one can’t help but wonder what Lewis would have thought of modern mega-churches and televangelism — but it still packs a wallop today. The film won three Oscars (for the acting of Lancaster and Jones, and the book adaptation by Richard Brooks), but lost the Best Picture award to The Apartment, as well as the Best Music Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture award to Exodus. Jean Simmons and Arthur Kennedy were denied Oscar nominations, although I think they deserved them. Lancaster and Jones won or were nominated for several other film industry prizes as well, and the film was, and remains, highly regarded. ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 22 January 2014.