Our fourth classic of 2014 is the Academy Award-winning Best Picture of 1932, Grand Hotel. It was a huge production for MGM at the time, reputedly the first movie to star more than just two or three top studio stars; this one has five, plus a couple of other roles filled with men who were stars in their own right. Whoever cast this film was absolutely brilliant and deserved a raise, for the concept of an all-star cast survives to this day and has only become increasingly prevalent, and because the film made a mint (the top ticket price for a seat was $1.50, which was astronomical for the time). It was the top box office attraction of 1932 and set new standards for its studio in terms of star power, grandeur and prestige. It is a film that greatly influenced the way that Hollywood did its business, immediately and ever since. Just five years after the introduction of sound recording, American cinema had reached what many critics — and audiences — considered its greatest pinnacle. Grand Hotel also holds an Academy Award distinction that will, in my opinion, never be approached by any other movie. It is the one and only Best Picture winner not to have been nominated in any other category!

Our fourth classic of 2014 is the Academy Award-winning Best Picture of 1932, Grand Hotel. It was a huge production for MGM at the time, reputedly the first movie to star more than just two or three top studio stars; this one has five, plus a couple of other roles filled with men who were stars in their own right. Whoever cast this film was absolutely brilliant and deserved a raise, for the concept of an all-star cast survives to this day and has only become increasingly prevalent, and because the film made a mint (the top ticket price for a seat was $1.50, which was astronomical for the time). It was the top box office attraction of 1932 and set new standards for its studio in terms of star power, grandeur and prestige. It is a film that greatly influenced the way that Hollywood did its business, immediately and ever since. Just five years after the introduction of sound recording, American cinema had reached what many critics — and audiences — considered its greatest pinnacle. Grand Hotel also holds an Academy Award distinction that will, in my opinion, never be approached by any other movie. It is the one and only Best Picture winner not to have been nominated in any other category!

Having established the altogether impressive historical credentials of this mega-production, we must now examine whether the movie itself is worthy of such fanfare. Because, after all, there have been plenty of movies over the years that caused furors and made boatloads of money but which have not withstood the test of time. Some of them, like Batman (1989) or White Christmas (1954) or Doctor Zhivago (1965) were never that great to begin with, in my humble opinion, yet struck sympathetic chords in audiences and are still remembered with fondness. Grand Hotel was an instant sensation and huge success, and was judged at the time to have earned its profits by skillfully blending its intersecting stories and incredible star power with admirable technique, solid storytelling and dramatic (and comedic) power. It does all of this and more, emphasizing its characters within the framework of the fancy Berlin hotel where, as Doctor Otternschlag (Lewis Stone) so famously comments at the beginning and the ending of the story to frame the action, “Grand Hotel . . . always the same. People come, people go . . . nothing ever happens.”

Grand Hotel introduces five major characters whose stories intertwine and collide in various ways during the two days or so they spend at Berlin’s most luxurious and elegant hostelry. The most famous is the Russian ballerina Grusinskaya (Greta Garbo), in town to perform but loath to do so to a half-empty auditorium. It is in this movie that Garbo murmurs her most famous line, “I want to be alone,” not once, not twice, but in three slightly varying iterations. Grusinskaya is like many stereotypical artists of high temperament, prone to spells of deep despair yet more than capable of intoxicating joy. It is to Garbo’s credit that she makes this flittery character so sympathetic and intriguing. The ballerina’s alarm regarding her Berlin performances is convincing, perhaps because Garbo seems too old to portray a grand ballerina in her prime (Garbo shared the same concern about her age, which was then 27). Yet, after her triumphant second performance, Garbo prances around her hotel room, fairly floating on air, bursting with confidence and energy. In this physical respect her performance is flawless.

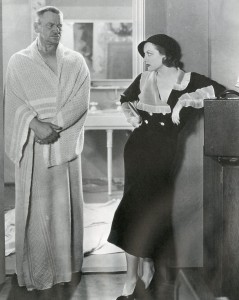

Much of Grusinskaya’s time is spent with a man she finds in her room at her darkest moment. He is the Baron Felix von Geigern (John Barrymore), an affable playboy rogue who find himself in heavy financial straits and attempts to steal the ballerina’s stash of pearls. In one of the film’s finest moments, which works because we do not really think he will confess, he comes clean to her about his intentions and returns her pearls. Then he has to convince her that his change of heart is because in the space of just a few hours he has fallen deeply in love with her. Although the film isn’t entirely convincing in this regard — I would have preferred that Grusinskaya display more suspicion and doubt, at least for a little while longer — her conversion is a happy one, for it brightens the film immeasurably. And for me at least, a happy Garbo is better than a depressed Garbo. Having something to look forward to in her personal life obviously brightens the dancer’s professional career; it is after her tryst with the Baron that Grusinskaya dances her heart out on the Berlin stage, earning accolades and fancy flower arrangements by the score.

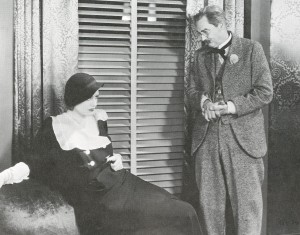

The other woman whose story is examined — and make no mistake, this is a women’s film, one of the earliest chick flicks — is the young stenographer, Flaemmchen (Joan Crawford). Flaemmchen is the first fish hooked by the playboy Baron, who arranges to go dancing with the young woman the next night, but by then he has fallen for the ballerina. Because she has no money of her own, Flaemmchen sees no alternative but to accept the clumsy advances of her current employer, the brutish industrialist Preysing (Wallace Beery), especially when he entices her with a trip to London and some new clothes. Her matter-of-fact acceptance of the situation, and all of the sexual connotations included with it, is surprisingly candid. Supposedly this resulted in some of Flaemmchen’s scenes being edited or removed in prints in some regions of the States, although such a thing can hardly be imagined today. Remember, this was 1932, still a couple of years before the Production Code was implemented, forcing cinema to adapt rigid rules regarding how characters could be presented and how evil must necessarily be punished by the final fade out. Grand Hotel was not bound by such restraints and provided an adult drama with real ramifications for its characters.

Joan Crawford was, by 1932, on a par with Garbo in terms of stardom, though her path to the top had been of a different nature. Where Garbo was considered the greatest actress of her time, “the Face,” Crawford was far more down-to-earth, raw, sexually provocative and not at all innocent and pure. Crawford had become, once talkies overtaken the popularity of silents, very popular in a very short time. There was, of course, a rivalry between Garbo and Crawford, and the production team at MGM was careful to keep them apart as much as possible. In fact, Garbo and Crawford are not in any single shot of the film together; their characters never interact the way the men do. I don’t even recall the two women even knowing about each other in the story. The studio was happy that way — Garbo wouldn’t be upstaged by Crawford, and vice versa — and their stories could play out separately.

The three men have their own stories as well. Baron von Geigern (John Barrymore) is a playboy adventurer short on funds, but always long on charm and goodwill. He is the sympathetic hero of the piece, despite his need to resort to larceny, and he is the character I will long remember. The irony is that despite his criminality the Baron is the only character who really knows how to treat people and how to get the most out of life. Everyone who meets him socially is the better for it. John Barrymore is excellent as the Baron, suave and yet never conceited. Barrymore cuts a very romantic figure, never loses his temper, and is completely authentic as the hard-luck playboy. He matches up very well with Garbo, and would make a strong romantic foil for Crawford, too. It also impressed me that the Baron has as much regard for his dachshund as any of his romantic conquests, although the dog deserves more attention than he gives it.

In high contrast, General Director Preysing (Wallace Beery) is neither suave nor aristocratic. He is a bully trying desperately to salvage a broken business deal before it ruins him. He is not too distraught or busy, however, to pressure his pretty new stenographer into some extracurricular “dictation.” Yes, that quote is in the movie. Beery is the only one of the main actors to utilize a German accent — he reputedly had it stipulated in his contract that he would be the only one to do so — and he is actually quite good in the role. He fits the uncultured character to a tee, never becomes too strident in his arrogance, is physically fit, and is even sympathetic at times. His is a nicely rounded portrayal of what in other hands could become an unmitigated villain.

The fifth prominent role is the bookkeeper, Mr. Kringelein (Lionel Barrymore), who demands to be treated with respect at the hotel during his dying days. With only a short time to live, he is determined to live well. He is befriended by the Baron and by Flaemmchen, but driven to distraction by Preysing, the director of the company where he slaves away, especially when Preysing insists on preventing Flaemmchen from dancing with him. Lionel Barrymore is more flamboyant than the other actors from the beginning, which is a bit grating, yet as the character grows that becomes less irritating. Barrymore’s best moments come in the final act, as the three men’s fates intersect tragically, and Kringelein finds strength he never knew that he had.

Director Edmund Goulding could have been content to simply film it like a stage play (the property had, indeed, been a play before being transformed into a film, and had been successful enough to pay for the purchase of its rights), but he and the MGM bosses wanted more. So the film is surprisingly cinematic, with wipe dissolves (some of them angled) between scenes, various high angles looking down toward the lobby, crane shots as characters move around near the railings and switch positions, and even a few shots from outside the hotel showing the lobby entrance and Grusinskaya’s very large automobile. The production design is outstanding from the lobby to each of the hotel rooms, especially Grusinskaya’s (which Garbo insisted be lit with a red tint to make it more romantic). When MGM later built its Grand casino and hotel in Las Vegas, it based its design on the lobby in this movie.

It is somewhat curious to me that the film is so German. Yes, the source material by Vicki Baum was originally German, and of course many Hollywood filmmakers emigrated from Germany before and during World War II, but this predates that. I am somewhat surprised that the piece wasn’t Americanized, moved to New York or Los Angeles, in translation. And it was, in 1945, when MGM remade the property as Week-end at the Waldorf, but I would have expected that treatment the first time around. That it was not Americanized in that way tells me that Hollywood filmmakers were simply more Continental back in the day, that they were comfortable with European influence and source material, and simply accepted stories as they were rather than trying to force them into more familiar forms as occurs today.

When I first reviewed this film in December 2001 (Volume 3, Number 2) as part of my overview of Oscar-winning Best Pictures, I awarded it ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2 stars and noted much of what I have written here. I also made a stupid comment that all of the characters seem to reside on the wrong floor; I don’t even know what I meant by that. What I do know is that a second viewing, a dozen years later, has improved this movie’s stock in my eyes. It probably deserves a four-star rating merely for its historical significance and impact, but the fact is that it is a very entertaining movie on top of all that.

Is Grand Hotel a classic? Absolutely. There had never been anything quite like it before, and it has been imitated a great deal ever since. It presents a handful of legendary performers at their best, delivering superb characterizations in a story that actually means something. It is vividly romantic and yet earthy as well, combining those elements into a mix that is engrossing and entertaining. There are all types of filmmaking, of course, but Grand Hotel probably epitomizes glamourous and stylistic early Hollywood storytelling better than any other. It is a landmark movie, a popular success, a genuine classic. Enjoy it! ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆. 3 February 2014.