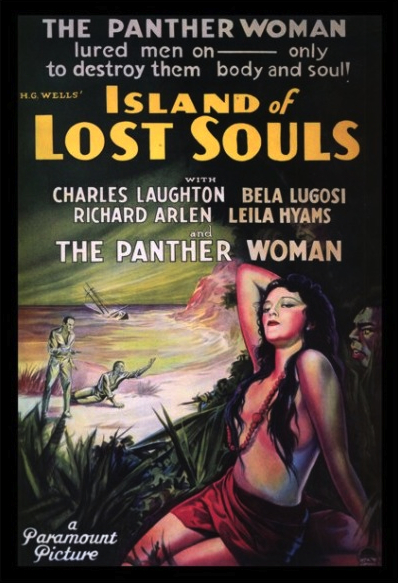

Our ninth classic of 2014 is an oldie — the first filmed version of H. G. Wells’ 1896 trenchant tale The Island of Dr. Moreau, which Paramount Pictures then retitled Island of Lost Souls when they produced it in 1932. Universal had opened the flood gates for cinematic horror the year previously with the blazing successes of Frankenstein and Dracula, so the rival studios quickly took notice and put their own tales of terror into production. This movie casts English actor Charles Laughton in one of his earliest Hollywood roles, although he had already appeared in another 1932 horror film, The Old Dark House. One year later, Laughton would be awarded an Academy Award for his portrayal of King Henry VIII in The Private Life of Henry VIII. But before that success, and before his triumphs in such classics as Mutiny on the Bounty, Ruggles of Red Gap, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Captain Kidd, Rembrandt, Hobson’s Choice, Witness for the Prosecution, Spartacus and Advise and Consent, among others, Charles Laughton played what is perhaps the ultimate mad scientist role in Island of Lost Souls.

Our ninth classic of 2014 is an oldie — the first filmed version of H. G. Wells’ 1896 trenchant tale The Island of Dr. Moreau, which Paramount Pictures then retitled Island of Lost Souls when they produced it in 1932. Universal had opened the flood gates for cinematic horror the year previously with the blazing successes of Frankenstein and Dracula, so the rival studios quickly took notice and put their own tales of terror into production. This movie casts English actor Charles Laughton in one of his earliest Hollywood roles, although he had already appeared in another 1932 horror film, The Old Dark House. One year later, Laughton would be awarded an Academy Award for his portrayal of King Henry VIII in The Private Life of Henry VIII. But before that success, and before his triumphs in such classics as Mutiny on the Bounty, Ruggles of Red Gap, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Captain Kidd, Rembrandt, Hobson’s Choice, Witness for the Prosecution, Spartacus and Advise and Consent, among others, Charles Laughton played what is perhaps the ultimate mad scientist role in Island of Lost Souls.

Laughton is Dr. Moreau, a British physiologist who had to flee England due to a controversy involving vivisection. It is on an uncharted island in the South Seas — latitude 15 degrees south, 170 degrees west — that Moreau establishes a laboratory where he can conduct gruesome experiments in seclusion and privacy. Wild, exotic animals are delivered to him there, for purposes unknown, and as a result, his island has the reputation of “stinking from one end of the South Pacific to the other.” This is the opinion of Captain Davies (Stanley Fields), the skipper of the vessel which delivers the animals. And on the current trip, the vessel delivers something else to the island — a man, named Edward Parker (Richard Arlen). Parker (Prendick in the novel) is the lone survivor of a shipwreck, rescued at sea and then unceremoniously dumped into Moreau’s schooner because he had the temerity to slug drunken Captain Davies in a fit of righteous indignation. Such indignation usually only occurs in the movies, and it almost always results in deep trouble for the indignator, in this case Parker, who is marooned on Moreau’s island for his trouble.

Dr. Moreau is cultured and refined, which only masks his almost total lack of humanity. Moreau has steeled himself against the suffering of others, particularly when that suffering is due to his own hand and instruments in the service of science. His obsession is almost total in regard to circumventing the slow, measured pace of evolution in order to create a new species of being. His actions seem vicious and sadistic, yet none of the horrible cruelty he inflicts is personal; he never means to spite or punish anyone or anything by the choices he makes. It simply never enters Moreau’s consciousness that pain, cruelty or suffering is important. He uses the threat of pain as a means of domination, but he never inflicts pain because he wishes to — it is merely a byproduct of his science, one that proves useful in regard to maintaining control of the subjects of his experiments afterward.

Parker is disturbed to learn that Dr. Moreau is a vivisectionist, which means that he operates on subjects without benefit of anesthesia. Parker witnesses such atrocity firsthand and confronts the doctor later, but then the movie’s first twist occurs. Parker assumes that Moreau is altering people to become the deformed “natives” whom he discovers on the island, and he is naturally worried that he will be the next victim. It is a natural mistake (and fear), because the natives speak, albeit haltingly, and act like men. But Moreau’s secret is deeper: he vivisects the exotic animals that he receives, attempting to turn them into humans. Moreau is trying to accelerate evolution in order to create a perfect human being, born of beast but turned by radical surgery and extensive training into something higher than man. And he has almost succeeded.

Moreau’s latest creation is Lota (Kathleen Burke), an exotic woman with Bette Davis eyes who is introduced to Parker as a “pure Polynesian”. The truth is that Lota is just like all the ugly, brutish “natives” who live in the jungle, save for her startlingly beautiful appearance and open hint of human feelings. Lota is the Panther Woman, and Dr. Moreau’s finest miracle so far. He is hoping that he has finally “beaten back the beast” and brought forth truly human aspects where there were none to begin. With the unwelcome arrival of Parker, Moreau divines an opportunity to learn once and for all if Lota truly has the emotions of a woman, and if she has the capacity to love. What happens to Parker later, of course, is of no matter.

The H. G. Wells source novel is philosophic regarding Moreau’s intentions. Should man elevate himself to godhood? Can human nature be bred, or inserted, or indoctrinated, into animal instinct? Does the march of science override concerns regarding suffering and cruelty? At what point does scientific obsession turn into madness? These and other questions bounce and rebound throughout the book, giving Wells the opportunity to discuss them at length, especially in regard to the Beast-Men, who are far more important in the novel. These concerns also appear in the movie, although rather fleetingly. It is, after all, a movie, and thrills and chills comprise the desired product, not intellectual stimulation. Wells was reportedly disappointed with the film, feeling that it substituted vulgar excitement for his more refined philosophical diatribes.

Wells failed to give credit, however, to where credit is due. As directed by Erle C. Kenton, Island of Lost Souls is a seriously creepy movie. Because it was made two years before the Production Code was instituted, the film has more than its share of elements that would have been altered, diminished or removed entirely had it been made just a few years later. It does not shy away from the cruel aspects of vivisection, even including a scene of such on the operating table that Parker interrupts. It introduces the interspecial character of Lota for the express purpose of making romance with Edward Parker, discovering once and for all if the creature that Moreau transformed from a panther can actually live and love — and presumably reproduce — as a human female. The bestial denizens of the jungle, led by the Sayer of the Law (Bela Lugosi) are deformed primitives, just barely human, waiting for the impetus to return them to their bestial natures and wreak havoc upon the man who has so hideously transformed them into caricatures of men. Such “natural justice” is common and expected in cinema, and the film follows the formula deftly, while Wells’ novel takes a longer, rather serpentine path to its antisocial conclusion in England.

Moreau dominates the Beast-Men with a whip, and with three important “Laws” he has drummed into their thick, hairy heads. They must walk on two feet. Are they not men? They must not eat meat. Are they not men? They must not spill blood. Are they not men? By these commandments — and their similarity to Biblical commandments is not accidental — Moreau is able to rule the ever-growing island population without fear. They fear his laboratory, the House of Pain, because he is able to transform beast into man, with varying degrees of success, and to return any one of them to its horrors if they transgress by regressing into bestial ways.

The Big Questions that concerned Wells are here in the film, in the furry ears, hooved feet, tapered fingernails and misshapen faces of Moreau’s subjects. Kenton’s visual representation of the lush jungle verdure, the rampant Moreau-induced plant growth inside his gated compound and the manner in which the lithe Lota, the ape-like Ouran (Hans Steinke) and the fierce, fanged M’Ling (Tetsu Komai) climb and scamper through it all suggests life and vitality — that nature will survive long after Moreau and his grisly experiments have passed on. This view is visually transposed with Moreau’s boxy white fortress in the midst of the verdant jungle, framed with iron gates and barred windows and shadows, vertical non-natural reminders of their cold, sterile inappropriateness. Nature versus the unnatural is the key motif of the movie, and it is clear from the first glimpse of Parker’s overturned boat to the fire that consumes Moreau’s laboratory that nature is going to prevail.

The film, however, is sadly prosaic in its use of the Beast-Men, making them ugly and creepy but maddeningly docile, ruled by their fear of Moreau and sanctions of the Law, until the climax when Moreau instructs Ouran to break the Law and then stupidly expects them to ignore his transgression. Other than Ouran, M’Ling and the Sayer of the Law, none of the beast-men are given anything to do but chant the Law and riot at the climax. There is a nice, brief sequence late in the film when six of the beast-men approach the camera quickly, one after the other, that produces both menace and shock value, but Kenton either neglected to or was not permitted to make the hideous beast-men even more menacing and frightening than they are. The Sayer of the Law is the most flamboyant of Moreau’s victims, given deference by the other primitives, yet even he is actually given little to do other than to repeat the Law that he has been taught. The ape-like Ouran shows more intelligence and guile. For fans of Bela Lugosi expecting something really special after Dracula, this role is a definite let down — although his hairy makeup, foreshadowing what Larry Talbot would eventually look like in The Wolf Man a decade later, is quite impressive.

Edward Parker is a rather conventional leading man / hero figure, although I find it odd that he tells Moreau that he could forgive the experimenting that produced every single beast-man on the island, but cannot forgive him for the only woman, Lota. He hears the cries and witnesses the cutting open of a screaming beast on the operating table — which initially revolts him — but is able to reconcile himself to Moreau’s madness until he realizes the truth behind Lota’s exotic personality. Perhaps people were merely more tolerant of medical craziness back in the day. The most intriguing character is that of Moreau’s colleague Montgomery (Arthur Hohl). Montgomery is Moreau’s right-hand man but has a conscience where Moreau does not. It is he who sends a cable to Parker’s fiancé, resulting in Parker’s eventual rescue. It is he who, upon learning that Moreau intends “to burn the creeping beast flesh” out of Lota, gently promises her that she will not return to the House of Pain. It is he who ultimately leads Parker and Ruth to safety, even at peril to his own life. Montgomery is the unsung character in all this, and he is played quite nicely by Arthur Hohl.

Because this is a movie, ultimately good defeats evil and Moreau’s evil empire burns in flames. The hero and his woman escape and the truth will be told about the doctor and his madness. Unlike many projects finalized under the Production Code after 1933, the road to the requisite happy ending is unusually rough and brutal, with a lot of controversial issues raised along the way. Movies like this, which raised questions about some very fundamental beliefs, and which sensationalized bizarre behavior and sexual candor were precisely why the Production Code was brought into being in the first place. Can you imagine how this movie might have played in the Bible Belt? It probably wasn’t seen in certain states at all.

Wells’ novel had been filmed as a French short film in 1913, but this was its first full-length treatment. It would be adapted again, unofficially, in 1959 in the Philippines as Terror is a Man with Francis Lederer as a Dr. Girard. A second unofficial version, again filmed in the Philippines, was The Twilight People, in 1972. It starred Charles Macauley as a Dr. Gordon, and a young Pam Grier as Ayesa, the Panther Woman. I have not seen either of these. The next official version appeared in 1977, under Wells’ original title, with Burt Lancaster as Dr. Moreau, Michael York as Braddock (Parker) and gorgeous Barbara Carrera as Maria (Lota). Directed by Don Taylor, it’s not bad. On the other hand, the 1996 version, again with the original title intact, is terrible. It shouldn’t be, not with John Frankenheimer at the helm and Marlon Brando as the crazy doctor, but it is. Not even the gorgeous Fairuza Balk can save it. This first version is still, easily, the best of the lot.

Is Island of Lost Souls a classic? Yes, although it has dated quite a bit. Its chief flaw, to me, is that its central core does not resonate. It seems decidedly foolish to try to create a perfect person from an animal. That premise was convincing in the book, but not so much in the movie. Everything else works very effectively, but it’s like a tree with a hollow trunk that sooner or later is due to collapse of its own weight. That it doesn’t fall is a tribute to the filmmakers; only looking back does the exercise seem fallacious. Yet this movie, flawed as it may be, is one of the cornerstone blocks of American cinematic horror. It is marvelously staged (filmed largely on Catalina Island), establishes a defining, enduring archetype of a learned, brilliant scientific mind bent and twisted into madness, and employs its grisly imagery in able support of its grotesque story. ☆ ☆ ☆. 28 May 2014.