Our eleventh choice for 2014 is this comic western adventure that delves into the mythology of Judge Roy Bean. It is William Wyler’s The Westerner (1940), which stars Gary Cooper as one of the few suspected horse thieves that Roy Bean doesn’t hang, and Walter Brennan as the Texas judge infamous for hanging anyone who crosses him.

Our eleventh choice for 2014 is this comic western adventure that delves into the mythology of Judge Roy Bean. It is William Wyler’s The Westerner (1940), which stars Gary Cooper as one of the few suspected horse thieves that Roy Bean doesn’t hang, and Walter Brennan as the Texas judge infamous for hanging anyone who crosses him.

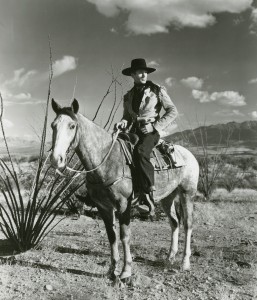

Gary Cooper didn’t want to take the role because Roy Bean’s character is greater in prominence, but he was persuaded to by the producer, Sam Goldwyn, under threat of a lawsuit. Cooper didn’t think there was much of a part for him, and he was correct — yet the fictional story needs a counterbalance to the Roy Bean character, and someone with some stature to provide it. It needs a character to serve as moral anchor, to see and express both viewpoints regarding the desires of cattlemen and homesteaders, and an actor who could share the screen with Walter Brennan without fading into the background. Cooper made the movie under protest, but he needn’t have worried; although Brennan certainly steals the show, William Wyler’s movie gives Cooper plenty to do and holds up more than eighty years later as a top-notch comic character study.

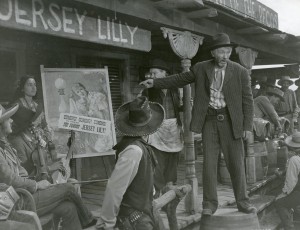

Western miscreants are brought to Vinegaroon, Texas to appear before “the hangin’ judge,” Judge Roy Bean (Walter Brennan). One such man is hanged as the story opens, more because Bean doesn’t like homesteaders than any evidence of guilt. Another man, Cole Harden (Gary Cooper), is ridden into town on a charge of horse theft; it looks bad for Harden because the horse belongs to Chickenfoot (Paul Hurst), who identifies it in the saloon which serves as a courtroom. Harden, who pleads his innocence, uses the last of his money to buy drinks for the jury (the men in the bar at the time), thus buying some time to think of a defense. He notices that Bean is a fan of English actress Lily Langtry and convinces the judge that he not only knows her personally, but owns a lock of her hair. Bean suspends Harden’s sentence with the understanding that the stranger will retrieve that hair and give it to him.

Harden is proven innocent when the real horse thief rides in and is dealt with by Bean, but the judge won’t let him leave. Harden has to trick him the next morning to get away, but the plight of the homesteaders, and particularly Jane Ellen Mathews (Doris Davenport), persuades him to stay in the territory. Harden makes a deal with Bean; he saves the judge from a lynching in exchange for cattle being removed from the homestead range — plus the lock of Lily Langtry’s hair. Bean keeps his end of the bargain and Harden keeps his, although the hair he eventually passes to Bean is really that of Jane Ellen. Peace, however, is short-lived because Bean has no intention of leaving the homesteaders alone. While they are celebrating his men burn the corn crop and the homesteads. Jane Ellen’s father is killed in the raid and all of the homesteaders except her pack whatever they can find and leave. Harden confronts Bean, who admits his complicity, exclaiming that the homesteaders will never settle on the cattle range while he is alive. Bean has also changed the town’s name of Vinegaroon to Langtry in honor of the Jersey Lily, who is scheduled to visit the area soon.

Harden rides to Fort Davis to be sworn in as a deputy and to obtain a warrant for Bean’s arrest; he stays in town because Lily Langtry is appearing there and he knows Bean will be unable to stay away. That is the case, as Bean rides to town in his old Confederate uniform and is the only person to attend Lily’s show (he has purchased all of the tickets). But instead of Lily Langtry on stage, the curtain rises to show Cole Harden, ready to make his arrest. After allowing the orchestra to escape, they have a gunfight and Bean is mortally wounded. But before the judge dies Harden carries him backstage to meet Lily. Later, Harden is shown with Jane Ellen in a new house, and they see settlers coming back to the range to turn the wild Texas wilderness into farming land.

The crux of the story — which is entirely fictional, like the character of Cole Harden — is the unusual and unexpectedly deep relationship that develops between Harden and Judge Roy Bean. Harden is sly enough to escape a hanging by playing on the judge’s fascination with actress Lily Langtry, and the judge is suspicious, but he respects Harden for standing up for himself as well as the tales he tells about Lily. Bean comes to trust Harden, especially after he warns the judge about the men coming to lynch him. Harden keeps the peace, which also impresses the judge, and although they have different views about the homesteaders Bean is willing to overlook that because of their shared interest in Lily Langtry. Their friendship is sealed when Harden finally gives him the lock of Lily’s hair — with Bean never knowing that it actually derives from the head of Jane Ellen Mathews. That is a secret that Harden will keep until the day he dies.

Bean also respects Harden for outfoxing him. After Harden clears his name they go drinking, awakening the next morning in the same tiny bed, with Bean’s arm around his shoulders. That little scene is the comic highlight of the film, as Harden tries to remember how he ever ended up in bed with the old man, and tries to crawl out of his embrace without awakening him. Harden almost sneaks away but Bean awakens and suddenly realizes that Harden is leaving without giving him the hair he promised. They tussle out in the desert and Harden insists that he is going to California. He only gets away because he sneaks Bean’s gun away without the judge noticing. This is my favorite scene because it illustrates that the friendship has already blossomed. After the judge tackles Harden as they race through the brush on horseback, Harden exclaims, “You mangy old scorpion, you could have killed the both of us!” Instead of taking offense, the judge laughs, and Harden smiles back. Their shared adventure has begun. Bean’s respect for his newfound friend is cemented when he discovers that Harden has stolen his gun, and another smile slowly steals across his face.

One other comedic aspect connects the two men: Judge Bean has a trick neck and Harden is seemingly the only person he trusts to straighten it out. This Harden does in several scenes, once by slugging him while they are sitting on the ground. The judge thanks him for it. The director, William Wyler, was drawn to the project because of the relationship between the two characters, and he described the film as “a comedy disguised as a melodrama.” While most westerns of the previous decade were short on characterization in favor of action and fast pacing, this began to change with Stagecoach and Dodge City in 1939. The Westerner focuses on how Harden is able to worm his way out of a hanging and then befriends the man who was ready and willing to do the deed. The film has just two gunfights, the horse race, the fire / raid sequence and one vigorous fistfight between Harden and Wade Harper (Forrest Tucker, in his film debut). Most of the film consists of dialogue rather than action, and this fact disappointed some critics of the era. The film was considered “artsy,” partly due to that lack of action but also because of Gregg Toland’s beautiful, evocative cinematography. While the film was lensed in just one month (in New Mexico, standing in for Texas), its budget was a fairly hefty two million dollars.

One of the few periodicals to truly appreciate the film (other than its acting, which was universally lauded) was Life magazine. Its commentary states the case much better than anything I can say: “In The Westerner, Samuel Goldwyn had perfect material for another pretentious epic of the West. Instead, he produced something much rarer and much harder: a real character study that may go down in movie history as a comedy classic. Expertly acted by Walter Brennan, Bean is a paradoxical renegade, big-hearted and cruel, weak and indomitable.”

I couldn’t have said it better. Wyler crafts the drama carefully, deftly establishing Bean’s rather careless disregard of life, before introducing Harden as yet another of his doomed victims of justice. But then the stranger uses his brain and plays with his one chance as if in a poker game. He reveals his cards gradually, one at a time, to the judge, upping the ante until the jury returns from drinking with the expected verdict. With the possibility of losing the chance to obtain a keepsake of his beloved Lily, the judge folds, allowing Cole Harden time enough to retrieve the hair, at which time he will likely still be hanged. Wyler keeps the camera in the saloon courtroom for almost twenty minutes (not quite continuously) after the film’s opening sequence, allowing the judge to establish his court, one man to die, and then Harden to sweet-talk his way into the judge’s good graces. That lengthy sequence includes a visit by Chickenfoot’s horse Pete, who is brought into the saloon as evidence, and who nods in affirmation when Chickenfoot asks Pete if he is his. It is also notable that in his position as judge, Bean has complete command of the law and explains its complex tenets clearly and indelibly upon those who run afoul of it.

Much of the comedy is almost subversive in nature, consisting of sly looks and bits of dialogue that have double meaning. Nothing is laugh-out-loud hilarious until Pete the horse nods along with Chickenfoot, or until Harden awakens with Bean’s arm around him. But the tone is comedic from the moment Harden buys the jury a bottle of booze and spies Lily Langtry’s pictures above the bar, one of which sports a bullet hole right through her teeth. Harden spills a little of the booze on the bar . . . and it bubbles! The undertaker measures Harden for a coffin . . . while he’s still standing at the bar, before the jury has returned. The jury goes into a back room marked “Table Stakes” . . . and someone turns the sign around to read “Jury Room.” The judge asks the jury foreman what the verdict is. “You know what the verdict is — guilty!” is the response. Such is life, and death, in Judge Roy Bean’s courtroom.

Judge Roy Bean was a real lawman who was infamous for his unusual rulings (but not hangings). The only other character based on reality is Lily Langtry, who appears in the final scene and has just one line. In reality, Lily only visited the town of Langtry shortly after Bean’s death (after a bout of drinking) in 1903. But in order to expedite the drama and provide a payoff, it was decided that Bean should be killed by the fictitious Harden, and that he should at least meet the damsel of his dreams before he shuffled off this mortal coil. Considering that this movie probably contains the most well-known and memorable portrayal of Judge Roy Bean, there must be many people who believe the judge was shot to death at Fort Davis. Indeed, the visual image of the curtain rising to reveal Cole Harden standing tall, hands on his belt, ready to arrest the judge, is the most indelible in the film. It is among the greatest images in American westerns, representing the good fight against tyranny and injustice. It is an image that helped Gary Cooper cement a solid western persona, despite the fact that he barely made a dozen of them in the thirty years after the end of the silent era.

Beneath the comedy, and underlining the actions of the nefarious judge, is the ongoing question of land use between the cattlemen who want to keep the range open and the homesteaders who want to fence and farm it. Bean is a cattleman through and through, using his power against the farmers at every opportunity. The farmers finally rise up against Bean en masse to rid themselves of his oppression once and for all, but Harden prevents the fighting by riding ahead and warning the judge. The stranger to the territory tries to persuade both sides that they can live together in harmony, having seen that battles between similar antagonists have been deadly in other areas. Bean plays along but gets his way later, when his men burn out the homesteaders and kill Jane Ellen’s father in the process. It is only when Bean acts against the homesteaders that Harden stands up against him and takes action. This larger conflict is never really settled, though the ending hints that with Bean’s death the returning settlers will be able to begin again.

Apart from the fine acting of the two leads and Gregg Toland’s gorgeous cinematography, the film is known for featuring the debut of Forrest Tucker, who would enjoy a long and fruitful career in film and on TV, mostly in westerns. Tucker plays Wade Harper, who seems to have an interest in Jane Ellen Mathews before Harden arrives, and who mixes it up with the stranger after he prevents the homesteaders from lynching Judge Bean. It was also the first of five 1940s teamings of Gary Cooper and Walter Brennan. They also appeared together in Meet John Doe, Sergeant York, The Pride of the Yankees and Task Force. On the other hand, Doris Davenport, who played Jane Ellen Mathews, only made one more movie before retiring, following a bad car crash which injured her legs.

Is The Westerner a classic? Yes! At a time when westerns were gaining industry respect and box office clout, William Wyler and Samuel Goldwyn took a chance by making one that inverted traditional ingredients, stressing character and dialogue instead of action, pace and formula. They persuaded sterling character actor Walter Brennan to portray the judge, which won Brennan his third Best Supporting Actor Academy Award in five years, a record of accomplishment which still stands today. They essentially forced Gary Cooper to accept a lesser role, but because the film was so good and popular, it helped his career as well. The movie also earned Oscar nominations for its writing and art direction. Its popularity served to spur the genre toward ever greater breadth and depth, while contributing an iconic portrayal of one of the west’s most infamous characters. ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 8 July 2014.