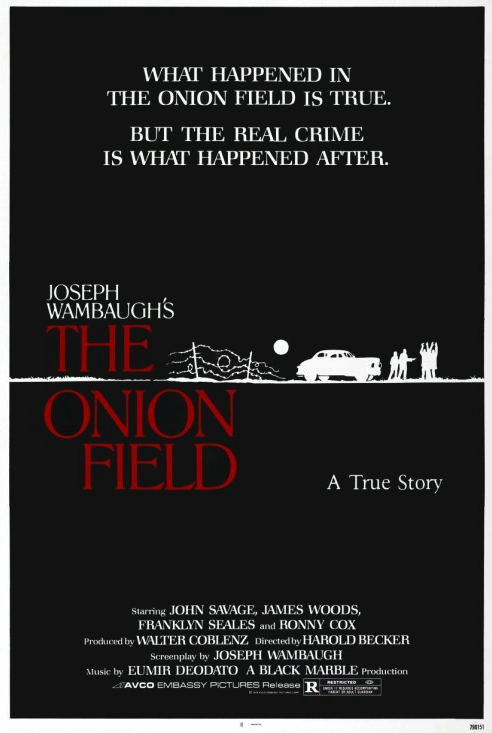

Our twelfth choice is the riveting 1979 crime drama The Onion Field, based upon the book by Joseph Wambaugh. In the 1970s Wambaugh became the dean of Los Angeles-area cop dramas, fueled by his experiences as a beat cop and detective sergeant. He worked in the L. A. P. D. for fourteen years, which also covered his first few years as a novelist. The Onion Field was Joseph Wambaugh’s third book, and his first foray into non-fiction. It chronicles a case which began in 1963 when two Los Angeles police officers stopped a car with two men and were taken hostage by those men. Later, at an onion field near Bakersfield, one of the policemen was shot and killed; the other ran and escaped serious injury. The men were caught soon afterward and a trial sentenced them to death, but their legal defenses and appeals dragged on for years, eventually removing them from death row. The book chronicles not only the original crime but the lengthy and rather astonishing legal moves that kept the killers alive. The book and film are as much, or more, about the aftermath of the crime than the crime itself, indicting the labyrinthine legal process that eventually propagated itself rather than serve justice.

Our twelfth choice is the riveting 1979 crime drama The Onion Field, based upon the book by Joseph Wambaugh. In the 1970s Wambaugh became the dean of Los Angeles-area cop dramas, fueled by his experiences as a beat cop and detective sergeant. He worked in the L. A. P. D. for fourteen years, which also covered his first few years as a novelist. The Onion Field was Joseph Wambaugh’s third book, and his first foray into non-fiction. It chronicles a case which began in 1963 when two Los Angeles police officers stopped a car with two men and were taken hostage by those men. Later, at an onion field near Bakersfield, one of the policemen was shot and killed; the other ran and escaped serious injury. The men were caught soon afterward and a trial sentenced them to death, but their legal defenses and appeals dragged on for years, eventually removing them from death row. The book chronicles not only the original crime but the lengthy and rather astonishing legal moves that kept the killers alive. The book and film are as much, or more, about the aftermath of the crime than the crime itself, indicting the labyrinthine legal process that eventually propagated itself rather than serve justice.

Director Harold Becker’s stylistic approach is low-key, semi-documentary realism, sensationalized only by the charisma of the performers and an ever-increasing sense of doom as two guys looking for an easy score attract the attention of two curious cops. Wambaugh, who not only wrote the screenplay but produced the film, was set on telling this story as it actually occurred, filming in many of the actual locations and recreating the legal scenes with the exact wordage used by everyone in court. Few films ever attempt such faithfulness to history and truth; fewer still succeed as well as The Onion Field.

One reason why the drama works so well is that its cop characters are not typical supercops. In fact, they have only just met — which proves to be a factor when they encounter a situation where they haven’t had to time to develop the instinctual trust that partners often do. These plainclothes officers, Karl Hettinger (John Savage) and Ian Campbell (Ted Danson), are still getting to know one another, seeing how the other responds to a whole realm of situations, and deciding whether it would be safe to risk his life either in service to or in protection of, the other. It’s a conditioning that all police partners experience, which can result in bonding friendship that lasts a lifetime or distrust and suspicion that must be addressed by supervision, often leading to new assignments. Hettinger and Campbell are still feeling each other out, so to speak, when fate steps in to accelerate the process.

A trio of Los Angeles-area criminals is, strangely enough, enduring this same process. Just out of prison, Jimmy Smith (Franklyn Seales), who also goes by the moniker of Jimmy Youngblood, has no friends and no money. The one man on the street that he knows is Billy (Lee Weaver), who introduces him to a slick hustler type, Greg Powell (James Woods). Powell and Billy have been doing small-time hold-ups, but Powell thinks Billy drinks too much and is a liability as a partner. Powell sees that Jimmy needs money and a place to crash, that he is young and spry, so he lends him some cash and enlists Jimmy to replace Billy on his nocturnal activities.

Jimmy has no intention of hanging around with Powell, but he cannot turn away from money and a room furnished by Powell. Reluctantly, Jimmy goes along with the situation, gradually replacing Billy as Powell’s right-hand man. Powell operates as the brains of their tiny little gang, casing liquor stores and altering his appearance before robbing them, but both of his black partners think he is a fool. Neither confronts him, however, because Powell has a mean temper and a big gun. Before Jimmy has a chance to forge an existence for himself he is caught up in Powell’s web of small time crime, as well as bedding Powell’s girlfriend (Beege Barkette). Jimmy tries once to drive away but Powell intimidates him into sticking around — and then they go on a fateful trip to knock off a liquor store for some quick cash.

A U-turn is what catches the eyes of patrolling cops Hettinger and Campbell. With nothing better to do, and enticed by the secret sense that their target is worthwhile, the cops turn on their flashing lights and pull over Powell’s car. Campbell’s reflexes are a little slow, however, and suddenly Powell has the drop on him. Hettinger is quicker, but he doesn’t want to start a firefight on a quiet city block, nor lose his new partner in the process. Tension mounts as Hettinger fights with himself, wanting to take action but knowing that if he does, people are going to die — perhaps himself. Ultimately, he gives up his gun to Jimmy, essentially signing their lives over to the two armed criminals. It’s a moment that Hettinger will live over and over and over and over again through the years, always wondering if he could have done something else. That long moment, stretched to tautness as Hettinger looks back and forth from Jimmy to Powell holding Campbell hostage, trying to will himself to action, is at the crux of the drama, and is beautifully staged.

From there the two hoods take the cops to the titular onion field outside of Bakersfield, where Powell says he will release them. But Powell knows the law, and believes that once the cops have been kidnapped, their kidnappers are eligible for capital punishment. So he gets there first, shooting Campbell in a jarring bit of violence that is still shocking despite being inevitable. In the confusion — Jimmy starts screaming in horror and four more bullets are pumped into Campbell’s chest — Hettinger runs and runs, somehow escaping the men hunting for him. His escape is realistic, but strange; at times he gives up completely, unable to move. Only the presence of a farmer (Le Tari), whom Hettinger feels he must also protect, gets him moving again. A few hours later, Hettinger leads other cops to the spot where they find Campbell’s body. The two criminals are captured in short order and neither denies the basic facts of the case. The only question concerns who shot the extra bullets into Campbell.

That question, which would seem moot in terms of common sense, becomes the legal lifeline for both men. Powell claims it was Jimmy; Jimmy doesn’t remember, but is heartsick that he could have done such a thing. As staged in the movie, it is hard to tell, but very possible that Jimmy was involved, or that both men fired shots into Ian Campbell. Nevertheless, the death penalty to which both men are at first sentenced is called into question because no one is sure of exactly who did what.

This leads to years of maneuvering, as Powell demands to defend himself and Jimmy is forced to befriend Powell again in prison to assure his cooperation. Lawyers on both sides come and go as the case drags on interminably. The case actually took eight years to fully adjudicate, making it, at the time, the longest legal case in the history of California. In the end, the state Supreme Court reduced their death sentences to life, and both men found themselves eligible for parole just a few years after this movie was released. Jimmy Smith was paroled in 1982, spent the next two-and-a-half decades in and out of prison and died in 2007. Powell was denied for parole at every opportunity and died in prison in 2012.

That last paragraph wraps up what really happened pretty quickly, but the film takes another hour to do so. Appeals by Jimmy Smith and Greg Powell are constant and, to the prosecution, immensely aggravating. With each new trial new defense counsel is used. Powell insists on defending himself. A district attorney (David Huffman) is so disturbed by the process that he quits and finds himself a new career. Karl Hettinger suffers the most. He is ostracized by the department, forced to discuss his actions that night from the perspective of being the wrong way to confront suspects. Guilt overwhelms him, leading to pilferage and massive pressure to resign from the force. Each new trial causes him to relive that tragic night, and in the film’s most poignant scene, he almost succumbs to his accumulation of guilt. Eventually, however, with the help of his wife (Dianne Hull), he learns to live with his past. Hettinger worked in the Bakersfield area near the end of his life, which occurred in 1994, years before the deaths of both of the men who had tried to kill him in 1963.

As terrible as the original crime is, the film’s position is that the legal mess that followed is just as awful because Ian Campbell’s killers do not receive the punishment they so richly deserve. Powell and Smith take advantage of the system, as they are permitted to do, so it is the system itself which is indicted by Wambaugh’s script. He is outraged that so many judges allowed the killers to run rampant in court, and that justice was overruled again and again by trivialities and dogged persistence by men who had nothing else for which to live. As Powell finds power in the legal process, Hettinger desperately tries to hang on to hope. There is innate drama surrounding this moral morass, and the film explores every inch of it, all the while maintaining its sober attitude and determined realism. Because this is a film, the drama ends upliftingly — Hettinger finds a sort of peace, finally able to connect with his wife again, as the two hoods face years in prison, and Campbell’s mother (Priscilla Pointer) achieves a sense of closure regarding her son. For Karl Hettinger, and Ian Campbell’s mother, the nightmare is finally over.

A drama this dense needs skilled performers, and Wambaugh and Becker chose well. James Woods bristles with nervous energy as Greg Powell; he earned a Golden Globe nomination as Best Actor for his work. Woods dominates every scene he is supposed to, and then looks devastated when Powell is told that he has misunderstood the “Lindbergh Law,” which is why he shot Campbell. I think Franklyn Seales is just as good as Woods; I was surprised when he didn’t receive the same acclaim, or an ascendent career. Seales contracted AIDS and died in 1990 at the age of 37. John Savage was one of the hottest actors on the planet when he made The Onion Field, having just made The Deer Hunter and Hair, but his next trio of movies flopped and his career never bounced back. He is excellent as guilt-ridden Karl Hettinger, especially in the scene with the baby and the gun. His ordinariness is just perfect for the role. Ted Danson shines in his few scenes, and Ronny Cox makes a strong impression as Sergeant Pierce Brooks, the investigator who steadily constructed the initial case against the killers.

Besides its delineation of the complex and troubling court machinations, the film excels in building its characters. The action doesn’t mean much if the characters are unconvincing or boring. Harold Becker ensures that each of the cast members gets the chance to show what they can do, whether it is the farmer (Le Tari) scared to death at the thought of putting his life in the hands of terrified Karl Hettinger as the cop killers roam nearby, or the dumpy defense attorney (Pat Corley), whose sloppy attire and monotone whining are skillfully designed to annoy the prosecuting attorneys to no end. This is a film dense with characterization, rich with layered depth and morally engrossing because of its complexity and overarching perspective. And all of it depends on the characters. Should Hettinger have given up his weapon? In yet another sharply written scene, one beat cop (Richard Herd) describes how he would have reacted, saying you do what you have to in order to survive. Moments later his boss decrees that any cop giving up his weapon is a coward. Both viewpoints are completely understandable, especially because we have seen the consequences. Yet the dilemma remains.

The events that transpired March 9, 1963 changed the way that police officers were trained to confront suspects, and how they were supposed to react given unfortunate circumstances. Joseph Wambaugh’s book describing that night is a well-researched, highly readable narrative of a collision of events that could not help but lead to tragedy for its participants. Harold Becker’s film translates these events and Joseph Wambaugh’s outraged perspective into engrossing drama brimming with rewarding performances and admirable grit. This isn’t a pleasant movie, but it is a classic one. Police methodology has changed over the years but the basic situation of cops mulling over a suspicious car will always be a powerful premise of dramatic promise. This version of that premise is memorable not only because of its skilled execution, but because of the sacrifice of a policeman who needlessly lost his life that night. The film is a moving tribute to Ian James Campbell, as well as other men and women who have followed his path. ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 9 August 2014.