This article was originally published in Filmbobbery in 2008 (Volume 9, Issue 4, pages 26 – 30). It has been updated for this website.

Much of the discussion in this issue has centered on cinematic “Essentials,” those movies universally acknowledged to be the best, most important and most representative of cinematic excellence. That designation does not apply to the tiny-budgeted, daffy, size-related movies of director-producer Bert I. Gordon, a man who has done his best to live up to his initials, Mr. B.I.G.. This article will explore the whys and wherefores of Bert I. Gordon’s obsession with size, both gigantic and miniscule, and how his singular cadre of movies evolved.

Born in Kenosha, Wisconsin on September 24, 1922, Bert Ira Gordon began making 16 mm films when he was nine, quickly developing a talent for innovative special effects to match his wild imagination. After graduating from the University of Wisconsin, Gordon moved to Hollywood and made commercials and industrial films while pressing studios for a chance to make feature films. Science-fiction and fantasy films — made quickly and cheaply — were all the rage at the smaller studios, and Gordon felt that he could do anything that anybody else was already doing, probably with greater speed and less cost. Lippert Studios was impressed enough with Gordon’s skill that they distributed, and profited from, his first feature.

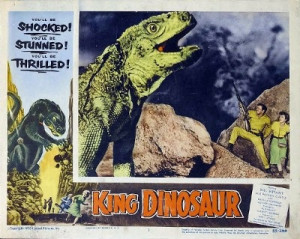

Gordon’s first feature, King Dinosaur (1955), cost just $18,000 to make and its principal photography was reportedly shot over just one weekend. It looks it. When a new planet invades our solar system, an intrepid crew of astronauts is dispatched to travel to it (in what looks to be a V-2 rocket) and make it safe for colonization. The new planet, “Nova,” looks a great deal like Earth, except that on an island the astronauts find a few dinosaurs, including a Tyrannosaurus Rex, the “King Dinosaur” of the title. The gigantic beast is destroyed by an atomic blast — the astronauts brought an atom bomb along, just in case they might need it — and the planet is declared safe for human colonization. My rating: ☆.

Filled with scientific errors, stupid characters, banal dialogue and poor special effects, King Dinosaur is a wretched film. Its most ludicrous feature is the title dinosaur, which in reality is an iguana. Take a good look at the lobby card artwork to the right, which promises a gigantic, angry dinosaur, and the film image, which delivers . . . an iguana. This is the central thesis of Gordon’s sci-fi career.

His principal tool became the matte shot, wherein regular size people are filmed acting and reacting to something, and a second exposure is made of the something, in this case, an unfortunate, stupefied iguana. The exposures are then joined, one on top of the other, with the result the the people are supposedly reacting to the iguana, although they’re not looking anywhere close to its actual location.

King Dinosaur was not an auspicious beginning to Gordon’s career, but it proved that he could (sort of) do what he claimed, and it made money. Gordon stepped up his efforts, tackling all aspects of production, from writing the story or screenplay to editing, creating and supervising visual effects, directing and producing. In essence, he became a one-man studio, and he had a great deal of fun bringing the whims of his imagination to fruition.

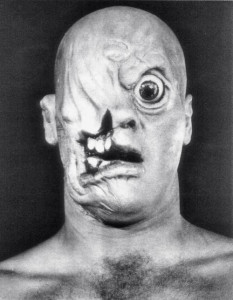

His second movie was not much of an improvement, but it set the structure for his “giant human” movies to come. The Cyclops was filmed in 1955 and released two years later through Allied Artists. It concerns a woman (Gloria Talbott) who finances a trip to the jungles of Mexico (actually the Bronson Caverns area of California) to find her fiancé, who has been missing for three years. Talbott and her three guides (James Craig, Lon Chaney Jr. and Tom Drake) discover giant animals and fauna, grown to gigantism due to radioactivity, but no fiancé. Then they run into a giant man with a disfigured face — the Cyclops of the title — who tries to kill them. They eventually dispatch him and Talbott realizes with appropriate horror that he was actually her betrothed. My rating: ☆.

Pretty awful all the way around, the film wastes its stars and never properly exploits its fantastic elements. The giant animals are all regular-sized beasts — a python, gila monster, iguana, falcon and gopher — filmed in close-up and enlarged to fill the screen behind the embarrassed actors. The actor playing the Cyclops is never even credited, although he has since been identified as former lifeguard Duncan “Dean” Parkin. The Cyclops make-up is fairly tasteless even by today’s standards, and his blinding demise is quite grisly for the time. Some of the special effects shots are pretty good, while others are ludicrous. In some shots, the Cyclops is almost transparent.

Recently The Cyclops has been remastered and issued on DVD through Warner Bros. Archive Collection, and shown on Turner Classic Movies, bringing a pristine print of this long-lost fright-fest to a new generation of horror fans. The movie still stinks, but now it looks really nice.

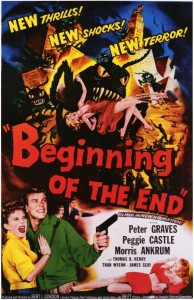

Gordon’s third film is just as silly as the others, but I must admit a fondness for its radioactive lunacy. In Beginning of the End, a 1957 release through Republic, grasshoppers eat radioactively-enhanced giant food in southern Illinois, grow huge themselves and then hop their way up to Chicago. Peter Graves and Peggie Castle follow, trying to find a way to limit their destructiveness. In the end, Graves uses the grasshoppers’ own mating call to lure them into Lake Michigan and drown them. It’s dopey fun with general Morris Ankrum delivering the classic line “You can’t drop an atom bomb on Chicago!” when discussing how to destroy the critters. My rating: ☆ ☆.

Male grasshoppers were imported from Texas to California for the filming, but they turned cannibalistic in transit, leaving Gordon with only a dozen or so left to film. Film them he did, walking through models of Chicago’s streets, crawling up pictures of buildings (sometimes right into the sky), and mindlessly marching into the pool that represents Lake Michigan. Beginning of the End is a stupid movie, but it has its charms. Peggie Castle is the model of modern feminine progress as a reporter, though she rarely seems to actually file stories. Graves’ assistant is a deaf mute, and when he is killed by giant ‘hopper, he soundlessly screams with terror. The battle scenes between the Army and the marauding locusts are intense.

Gordon once again ignored the scientific implications of his film. If the radioactive food caused the grasshoppers to grow, what would it do to the people who were the food’s intended destination? And once the grasshoppers were lured into Lake Michigan, wouldn’t the fish that ate them grow as well? Wouldn’t the world’s food chain be permanently altered?

The giant bug cycle was winding down when Gordon made this movie; all the “cool” bugs had already been utilized, so he chose grasshoppers. This did not prevent the studio marketers from emphasizing insect terror, as seen in the wonderfully evocative poster image above.

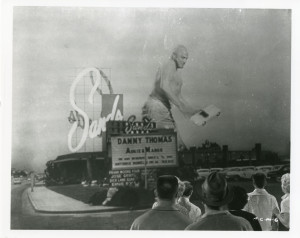

Gordon’s fourth motion picture is his most assured, and it interestingly parallels Jack Arnold’s masterpiece, The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), while going in the opposite direction in terms of size. The Amazing Colossal Man, a 1957 American International Pictures release, posits that an atomic “plutonium” explosion causes Army colonel Glenn Langan to begin growing at a phenomenal rate. He is soon about sixty feet tall and in great health (the bomb explosion has healed him completely) except for his heart, which is growing at a much slower rate and will eventually explode from the strain put upon it by his unwanted new bulk. Angry at the world for his condition, Glenn eventually loses his mind (because his heart is not pumping enough blood to his brain), escapes and stomps around Las Vegas, ripping the city apart before a final confrontation with the Army at Hoover Dam. My rating: ☆ ☆ ☆.

Probably because he had Arnold’s film to imitate, Gordon was able to infuse The Amazing Colossal Man with psychological depth, some decent special effects and a real feeling for its protagonist. Glenn Langan is not the monster that rampages through The Cyclops; he’s a real person trying to cope with an amazing physical change, and the film reflects that battle rather adroitly.

Some of the special effects are very poor; Glenn seems transparent as he walks through the matte shots of Las Vegas, but the model work is pretty strong, and the scene with the giant-sized hypodermic needle is unforgettable. Another highlight is the plutonium blast, during which Glenn is trying to save a downed pilot. The blast sears the skin off of Glenn but leaves him standing; it’s quite shocking and effectively done. Glenn Langan is good as the ever-growing giant, ably supported by Cathy Downs and William Hudson as the people who still care for him, despite his frightening condition.

Unfortunately, the success of Universal’s The Incredible Shrinking Man persuaded Gordon and AIP to follow in its footsteps, with the result being the totally ridiculous Attack of the Puppet People (1958). For the first (and only) time, Bert I. Gordon made a movie with elements substantially smaller than real life.

Puppeteer-turned-doll maker John Hoyt is a lonely old codger, left by his wife long ago. When his assistant, John Agar, announces that he shall be marrying Hoyt’s secretary, June Kenney, Hoyt refuses to let them go. He shrinks them to the size of six-inch dolls and pops them into glass tubes. Whenever he is bored, Hoyt brings out his “puppet people” and watches them, talks to them, and tries to dissuade them from escaping. Hoyt’s collection expands and eventually includes a couple of teenagers, a Marine, a mailman, a floozie and a couple of other people. Hoyt eventually brainstorms the idea to have his captives perform (for him only) a live puppet show. Two of the living dolls escape and end his reign of lonely terror. My rating: ☆.

Just how does a puppeteer (!) determine how to shrink human beings? And given this great scientific breakthrough, what does he do? He shrinks people to keep him company, forcing them to perform puppet shows! If this isn’t the stupidest idea for a science-fiction movie in history, it’s got to be awfully close. The film ends with two of the puppet people using Hoyt’s machine to get back to normal and leaving, hopefully to contact the authorities. The fate of the others remains unclear.

John Hoyt actually gives a sensitive performance as the lonely puppeteer and reportedly thought quite highly of the film. Another (weird) highlight is the song “You’re My Living Doll,” a rock ‘n roll ditty sung by Marlene Willis, which blandly restates the themes of the film (“Don’t deceive me / Never leave me / Stay with me forever / My living doll”). The special effects range from terrible to not bad, with lots of large props and sets providing the opportunity to make the actors look properly tiny. But the basic story is horrible, removing any charm the picture might be able to generate.

From there it was back to the formula for Gordon, as he directed his first (and only) sequel, War of the Colossal Beast (1958, AIP). A totally unnecessary follow-up to The Amazing Colossal Man, the film boasts a whole new cast. Having somehow survived his fall off of Hoover Dam, giant Glenn Manning (now played by Dean Parkin with makeup reminiscent of his Cyclops role) is found in Mexico raiding food trucks to survive. The military captures him, hoping to reverse his condition, returns him to Los Angeles and recruits his sister, Sally Fraser, to try to humanize him. Naturally, the giant escapes, and is cornered at Griffith Park Observatory. He threatens to destroy a bus full of teens, but is persuaded not to by Fraser. Instead, he ends his pitiful existence with some handy power lines. My rating: ☆ ½.

This plays more like a remake of The Cyclops than a continuation of the Amazing Colossal Man story. The makeup for the giant is eerily similar, needing to show the damage to Glenn after pitching off Hoover Dam. However, there is little if any evidence of the hail of bullets which sent him off the Dam to begin with. The makeup also forces Glenn into a brutish state. He can barely speak, and doesn’t seem human, just like the title character in The Cyclops.

The film has other problems. Dean Parkin and Sally Fraser are simply not the actors that Glenn Langan and Cathy Downs are. Fraser is said to be Glenn’s sister, even though the first film mentioned that he had no immediate family. The trick photography employed by Gordon is below even his usual low standards, and the big electrical finish, filmed in color, is silly beyond words when the body completely disappears.

A little bit better is Gordon’s next project, his final sci-fi project of the 1950s. Earth vs. the Spider, also made for AIP in 1958, posits a gigantic spider living in a cave near a small town (the cave is, believe it or not, actually Bronson Caverns again). When one teenage girl’s father goes missing, she and her boyfriend discover the spider and barely escape its grasp. Local authorities and an exterminator are called and succeed in poisoning the hideous beast. For lack of a better solution, the thing is toted to the local high school and put on display. There, a teenage rock group awakens it with noise and it rampages the town. The science teacher finally goes after it with electricity in the cave, just in time to save the teenage girl and her boyfriend, who have been trapped there with it. My rating: ☆ ☆.

Gordon’s film is, just like all of his other opuses, filled with scientific inaccuracy, stock characters, inane dialogue (especially the jive spoken by the teenagers) and special effects that vary from ridiculous to not so bad. The thing that Earth vs. the Spider has going for it is, as described by critic Bill Warren, elegance. “Earth vs. the Spider is so simply conceived that it verges on elegance, in the mathematical sense of the word, but is still silly and shoddy.” There is nothing extraneous in the film; nothing to impede its progress or distract from its theme. No scientific mumbo-jumbo about the origin of the giant spider; no excess whatsoever. In that regard, this is Bert I. Gordon’s best film.

It is fairly effective as a shocker, and it was a favorite of mine when I was very young. Perhaps the reason it still holds up well is because it is similar to another Jack Arnold movie, Tarantula (1955). Both films feature giant arachnids tearing up a small town, and both are clean-cut, simple survival stories. The title character is indeed a tarantula, filmed by Gordon meandering around model sets and photographed against the backdrop of Bronson Caverns and Carlsbad Caverns. Note how well-lit the caverns remain after the teenagers become trapped. Gordon had one spider leg constructed and used it several times during the film’s second half to reinforce the illusion that the spider was in the same frame as the actors. This ploy might have worked had there been one more than one leg.

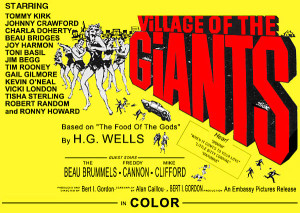

This was the last of Gordon’s sci-fi efforts in the 1950s, as the monster / giant human / giant bug cycle was fading. But it was not the last of Bert I. Gordon. He turned to fantasy and horror for awhile, directing The Boy and the Pirates and Tormented in 1960 and The Magic Sword in 1962. In 1965, Gordon made another stab at his favorite theme. He had long wanted to make a movie of H. G. Wells’ seminal novel The Food of the Gods, which details human gigantism and its social repercussions. He tried to mate the original Wells story with the hottest craze at the time, beach movies.

The result is the nutty, semi-erotic Village of the Giants, a zany movie with terrible special effects wherein teenagers Tommy Kirk, Johnny Crawford, Beau Bridges, Ron Howard, Tisha Sterling, Joy Harmon, Toni Basil and others ingest a substance which causes them to grow to 30 feet tall. Naturally, they run rampant over their town, dancing like mad and generally raising hell. Watching the giant bikinied girls dancing around in slow motion gave Gordon a new kind of audience, one he exploited as a producer with much sexier features in the late sixties and early seventies. Like most of Gordon’s films it made money, but no one over 25 paid it any serious attention. My rating: ☆ ½.

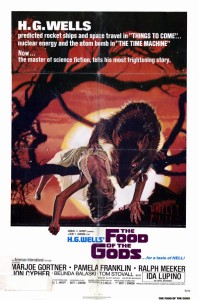

Gordon the director returned to horror with Picture Mommy Dead in 1966 and Necromancy in 1972, and made a timely thriller called The Mad Bomber in 1973. He was always looking for a trend to exploit. Not satisfied with his initial H. G. Wells adaptation, he made The Food of the Gods in 1976 and followed it with another Wells adaptation, Empire of the Ants, a year later. But he couldn’t afford the special effects for giant people so for both films he simply focused on giant predatory rodents and bugs.

The Food of the Gods has ordinary animals growing to giant size due to a strange substance found on a Canadian island. Wasps, chickens, worms and finally rats get the Gordon close-up treatment, eventually feeding on much of the surprisingly familiar cast: Marjoe Gortner, Pamela Franklin, Ralph Meeker, Ida Lupino and Belinda Balaski. As a horror film it is appropriately revolting, though not particularly suspenseful. My rating: ☆ ½.

Empire of the Ants is even worse. Florida real estate maven Joan Collins is trying to sell swamp land but she is unaware that local ants have eaten radioactive waste and grown to the size of Volkswagens. Not only that, but they have developed telepathy and can control humans to some degree. Fisherman Robert Lansing comes to Collins’ rescue and saves the local folk who have been under the giant ants’ spell. The plastic ants look phony and the story reflects little of Wells’ originality. The actors look appropriately grimy because the filming in the Florida swamps was exceedingly difficult, especially on Collins. But the film is pretty terrible. My rating: ☆.

Gordon went back to the occult for Burned at the Stake (1981), then churned out sex comedies: Let’s Do It (1982) and The Big Bet (1985). His final film was Satan’s Princess (1990), a mix of sex, sadism and witchcraft. None of his later films have had any lasting impact; he will always be remembered for his earlier sci-fi efforts.

Just what drove Bert I. Gordon to make so many movies involving gigantism? He has not openly discussed it in any of the profiles and interviews that I have read, so I shall do my best to surmise. When he first began making movies as a boy, he became deeply interested in effects work: ghost effects, people appearing and disappearing, editing tricks. Gordon found that he could make passable, sometimes startling, special effects shots himself that he felt rivaled Hollywood filmmakers’. His Hollywood career was based on that talent — creating special effects quickly and cheaply. He relished the challenge of using ordinary elements to create an extraordinary tableaux, even when it wasn’t particularly convincing to discriminating audiences. His target audience was the viewer who loved that type of movie, kids and adults who would forgive technical flaws as long as some thrills were delivered. To some degree he succeeded. So while most of his films are pretty lame, fans such as myself will always have an affection for what he was trying to do, and what he actually did.

Gordon made a successful niche for himself and was able to contribute to the Hollywood tradition he loved. Mr. B.I.G. returned again and again to the theme which enthralled him, attempting to concoct new ways to depict and stage larger-than-life threats against humanity, usually from the most common of elements found on Earth. All creatures great and small had the opportunity of becoming greater than ever in the hands of Bert I. Gordon.

And no one else ever dared posing the concept of dropping an atom bomb on Chicago to destroy a horde of marauding grasshoppers!