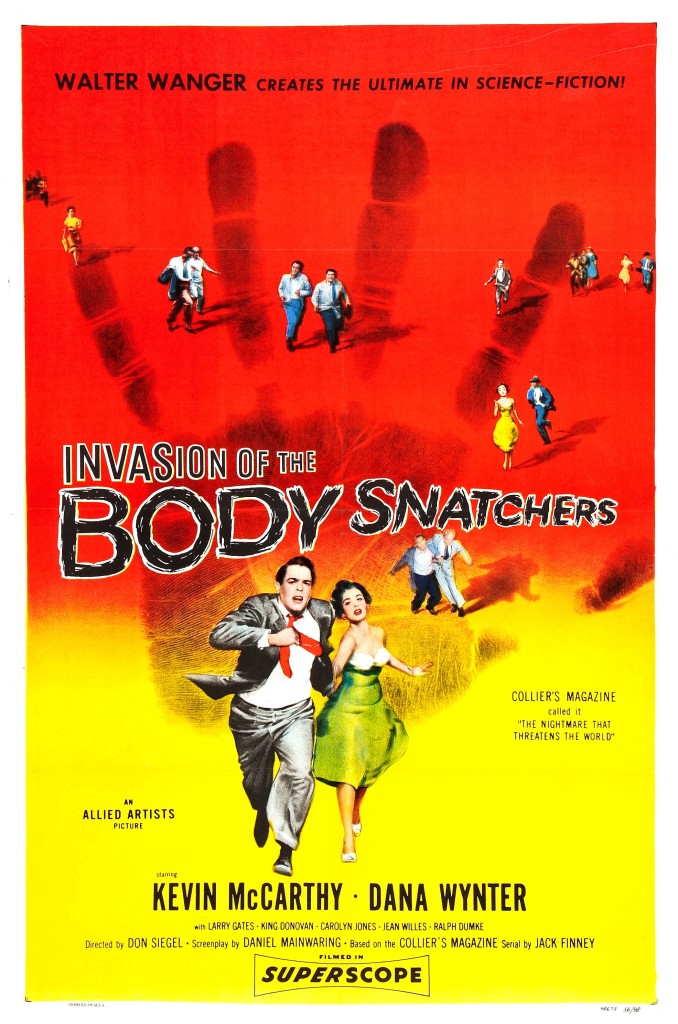

We return to 1950s era horror and science-fiction as we consider the first cinematic version of Jack Finney’s seminal magazine serial and novel The Body Snatchers. Indeed, that lurid, rather clumsy title has, along with the “Invasion” added by the film studios which purchased the rights to the story, part of our cultural zeitgeist. And while the serial and novel were certainly popular, it was the 1956 film, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, which, as insidiously as the pods themselves, gradually awakened the populace to the notion that losing our individuality was not just a cool sci-fi premise but an imminent threat.

Science-fiction at its best uses the trappings of scientific progress, space travel, the acceptance of alien life and other high-falutin’ ideas to examine and expose important human traits, flaws and aspirations. Dazzle the eyes with wonder but have a message to deliver along with the colorful creepies. In this case visual wonder takes a back seat to the very slight, almost indiscernible feeling that something is amiss — until events accumulate into something that can no longer be denied.

It all begins slowly in Santa Mira, California, when Dr. Miles Bennell (Kevin McCarthy) returns from a vacation to find that a strange malady is sweeping through his community. Suddenly relatives don’t seem to be relatives any more — and then just as suddenly, they do again. A form of mass hysteria, perhaps? Bennell has no idea until a friend calls upon him to witness something unbelievable firsthand. Jack and Teddy Belicec (King Donovan and Carolyn Jones) have found a “blank” body in their home. It isn’t alive, but it certainly looks to be forming itself into a person. Bennell examines it and notes some similarities to Jack. Bennell tries to call out of town for expert help, but when the phone lines are said to be busy, he suspects a dangerous conspiracy.

Bennell begins to link certain things in his mind, and soon he has found blanks for his girlfriend Becky (Dana Wynter) and himself, as well as the pods from which the blank bodies seem to originate. He learns that sleep triggers the switch from person to “pod person,” and that once the switch is made, it seems to be permanent. People replaced by their pod doubles are calm, logical and cannot be deterred from trying to replace everyone else around them. After capturing Bennell and Becky a couple of pod people tell them that switching over to a collective intelligence brings ultimate peace and tranquility — there are no more differences which divide people from one another. Of course, that also means a complete loss of personal freedom, of choosing one’s own destiny. So Bennell and Becky fight and flee, hoping to escape Santa Mira and warn the world about this impending inevitability of involuntary surrender.

It is easy to extrapolate larger meanings from such a premise, which is exactly what happened. Critics of the era, and many more so later, commented upon the similarity between Finney’s pods and the socio-political systems of socialism and totalitarianism, where one pledges everything, including all personal freedom, to the State. Even more recognized the efforts of Senator Joseph McCarthy to stifle free speech and thought in the actions of the spores from space. The film itself never makes such grandiose comparisons, but the allegory is clear, and it truly resonated back in the era of Cold War tensions. Even people who didn’t make connections to communism or McCarthyism were unnerved by the possibility of losing one’s hard-earned freedoms so easily, without even being able to put up a fight.

Being human means being able to make choices, good and bad. Mistakes are part of the process. Mistakes, and how we react to them, define us more than our achievements. Any system that neutralizes or eliminates our ability to choose, to ask questions, or to challenge, is as un-American as it can be. That is the paranoia that this movie taps into. That some weird alien pods could replace us with soulless lookalikes which, when they take over for us, know our lives inside and out but have no desire to continue our existence for any other purpose other their own replication. That love would quickly and simply disappear. That our very lives, so important to us, would become instantaneously meaningless, after merely falling asleep.

It’s a great, terrifying concept, wonderfully realized within the medium of science-fiction. It’s why this idea proved to be eternally popular, with four film adaptations made, beginning with this one. In its initial form, writer Daniel Mainwaring, director Don Siegel and producer Walter Wanger were merely trying to scare viewers silly, removing most of the piece’s humor and telling the story straight — without any prologue or epilogue. That’s right — originally the film began with Dr. Bennell returning from vacation and ending with him on the highway trying (vainly) to warn the people of the impending threat. It was only after test screenings and second thoughts by Wanger that the framing prologue and epilogue were filmed and added, turning what would have been an extremely pessimistic (but wonderfully effective nihilist version of America) into a cautionary tale.

The framing structure, thus telling the story in flashback, provides a critical distance to the material, reducing its horror impact and providing an assurance of safety at the end. Without the epilogue in particular, the story ends as an unfinished nightmare. While such tales are told today, it is pretty clear that audiences of 1956 were not yet considered ready for such shocks. Had the film been released as planned, it is fascinating to consider what the reaction would have been. It is certainly arguable that it would have been better, and a bigger hit. But maybe not. I actually like the framing device, but perhaps I’m just accustomed to it.

When I was much, much younger, I disdained this film, thinking that “pod people” were just too silly for words. At some point rather soon afterward I began to see the film in a different light, probably when I began to appreciate the leanness and clarity of Don Siegel’s work. I developed a critical eye, and began to see what others had seen and praised. At this point I’ve seen this film perhaps a dozen times, and it gets better with each viewing. At its center is an insidious presence from space, almost as cool as the Blob, that threatens humanity. And loss of humanity is what this film is all about.

Is Invasion of the Body Snatchers a classic? Absolutely! It is one of the finest science-fiction tales ever told; it is one of the best films of its year (1956); it is a harrowing story that has been made three further times, all resulting in good movies as well. It is a Cold War classic that conveys a hellish fear of the era, when the Korean War ended and brainwashing became a hot topic in the news. It is a beautifully crafted suspense thriller even with the prologue and epilogue; when considered without those elements it is a terrifying horror show. It is a film which, because it came from lowly Allied Artists, was not taken as seriously as it should have been, but one which proves that good films can originate from anywhere. It is a film with a silly, lurid title that belies its serious, frightening core. It is a genuine classic of the cinema, which happens to represent my favorite genre, from my favorite decade of film. ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆. 29 December 2015.