Of the really good movie crop of 1976, which includes All the President’s Men, Network, Rocky, Taxi Driver, Carrie, Marathon Man, The Shootist, The Outlaw Josey Wales, Silver Streak and The Pink Panther Strikes Again, to name some obvious favorites of my own, it is Network that seems the most prescient forty years later. I’m not the only one who feels that way; writer Aaron Sorkin has said, “No predictor of the future — not even [George] Orwell — has ever been as right as [Paddy] Chayefsky was when he wrote Network.” It’s a film that was way ahead of its time, so much so that it was generally considered to be satire upon its release even while writer Paddy Chayefsky and director Sidney Lumet insisted that it was seriously reflective of its era.

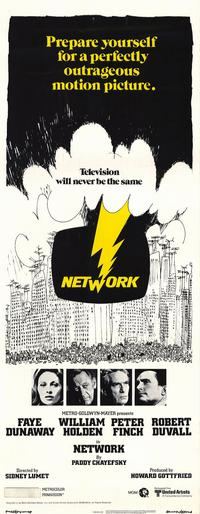

Network (1976) is an acerbic glimpse behind the cameras of modern-era television. Its first image is of four grand old anchormen in TV news: Walter Cronkite, John Chancellor, Howard K. Smith and Howard Beale (Peter Finch). Three were real, of course, and this opening image which introduces Beale, reporting the news for the fictional UBS network (a precursor of Fox), is meant to be as venerable as the others. The movie’s first shock, then, is that Howard Beale, due to low ratings, is going to be let go. Fired, in fact, due to his age.

Unlike his colleagues, however, Howard Beale is a loose cannon. He calmly tells his TV audience that his presence has been deemed unnecessary, and announces that he will kill himself on his show the following week. His producers, watching from the control booth, don’t even notice. But Beale’s proclamation becomes national news, and he is fired forthwith. But his best friend, producer Max Schumacher (William Holden), convinces everyone to give Beale another chance, and to end his run with dignity. That doesn’t happen.

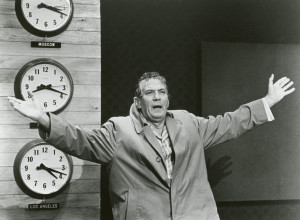

Instead, Howard Beale lets loose everything he’s been holding back, perhaps for years, slamming the TV station and its executives, the destabilization of news in favor of gossip and entertainment, and the medium of television itself. Before he flames out, Beale says exactly what is on his mind, using language that the FCC will be sure to condemn and fine. Beale is done. And yet . . .

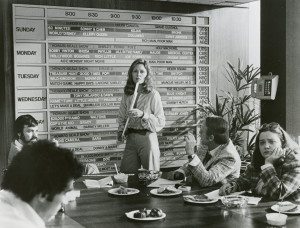

And yet, he isn’t. Ratings are through the roof. People identify with the new Beale, a man unafraid to speak the truth, or at least his version of it. An ambitious executive named Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway), argues that Beale should be given his own show, sort of a “bully pulpit,” and that she should produce it. She turns Beale into an oracle of protest, lets him say what he wants as long as it is contentious and controversial, and builds an entire block of television programming upon radical ravings and counter-cultural criticism. The hardest notion to swallow about all of this is that such shows would be able to generate and sustain their popularity over time, but the more recent popularity of “reality TV” proves that people will watch anything.

Another exec, Frank Hackett (Robert Duvall), uses Beale’s conversion from news anchor to prophet to gut the news division, firing Max and moving everything news-related under the “entertainment” umbrella of UBC. This is where writer Paddy Chayefsky was so prescient — he foresaw that unprofitable news divisions would come under increasing and constant pressure to turn news into entertainment. Granted, he didn’t seem to foresee it quite the way this evolution has occurred, yet he could see the change coming. He seemed to think it would go even farther, judging from the shows that Diana Christensen develops, but that is where the satire leads.

All of this is industry-level action and critique, and it is very trenchant and witty and scary (especially when network honcho Arthur Jensen [Ned Beatty] gets involved and starts telling Beale what to prattle about). But the film itself wouldn’t work if this were its only level. So director Sidney Lumet and Chayefsky ensure that the personal stories are just as important. Beale finds the most unexpected success of his career and quite possibly loses his mind (it’s very debatable). Max cannot save his friend Howard, but also cannot keep away from Diana and starts an affair that may very well end his marriage. Diana worships Max professionally, enough to sleep with him and keep him in the loop regarding Beale. Max’s wife (Beatrice Straight) is distraught at losing her husband’s attention to Diana, but tries very hard to hang on to her dignity. And so on and so on.

In the end, all of the craziness can only be judged by what occurs to the characters. Change takes place, certainly, but people still have to work and live and love and die. Beale’s career as a prophet of the airwaves finally comes crashing down; Max leaves his empty relationship with Diana to return to his wife, if she will have him back; Diana moves on to her next professional challenge, possibly with Frank Hackett; UBS looks for its next hit show. The world carries on.

This is a comedy? You bet it is. It’s a comedy of the sublime, of the ridiculous, of excess and of fearless wit. It isn’t so much a laugh-out-loud belly-laugh comedy as it is a jaw-dropping expression of bad corporate behavior that, at its worst, approaches insanity. Diana negotiates with bank robbers for their own television series, then later has an absolutely surreal scene where everyone involved dickers over ratings, points, subsidiary rights and distribution charges. Or, consider Howard Beale’s exit strategy at the end of each episode of his hit show. After an hour of sustained ranting, he makes his final dramatic point and then simply keels over, collapsing in a ludicrous paroxysm, crumbling to the floor and lying there seemingly oblivious while the studio audience bursts into wild applause. Finally, of course, there is the terrific wit, written by Chayefsky and delivered by its award-winning cast. Like when Max describes Diana: “I’m not sure she’s capable of any real feelings. She’s television generation. She learned life from Bugs Bunny.” Or when Arthur Jensen tells Beale he has chosen him to deliver his corporate gospel to the masses. “Why me?” asks humbled Howard. Jensen replies, “Because you’re on television, dummy.”

But I believe that the main reason people connect with this film isn’t the satire, or the wit. It’s the wisdom. Howard Beale rants, and a lot of it is bluster, and yet people both in the movie and watching it identify with his hysterical righteousness. The catch phrase that became famous is “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” Everybody has felt that way, and evidently a lot of people feel that way a lot of the time. Government, corporate America and the powers that be have failed us again and again, and here is one man, begging and daring us to stand up and voice our frustration. Of course we’re going to connect with that message. Beale’s other diatribes also contain truth, although his audiences seem to appreciate his delivery and exasperation as much as his message. The irony is that the TV honchos don’t care at all what it is that he’s saying — even when he begs his audience to stop watching TV and go live their lives — as long as he keeps delivering ratings.

Barb and I had a lively discussion afterwards as to whether Howard Beale is, or goes, insane. She felt that he never quite loses touch of his sensibilities, though he may be somewhat “lost.” I lean more toward thinking that Beale finds success in being outrageous and simply allows himself to be increasingly outrageous until he can no longer stop, or realize that he has crossed into insanity. I’m not sure he’s ever completely crazy but it seems clear to me that, by the end, his mind is no longer, um, clear. Does it matter? Probably not, but the answer may define how you react to the film, especially the conclusion.

Network is brilliantly written by Chayefsky and beautifully directed by Sidney Lumet. Having begun his career in television before moving into feature films in the 1960s, Lumet was the perfect guy to direct this story. He remembered how television was first-hand, because he was one of the people responsible for it. Lumet was an actor’s director; counting Network Lumet has guided seventeen different performers to Oscar-nominated performances (five of them coming in Network). He believed passionately in this film and was outraged when Rocky beat it to the Best Picture Oscar. Network may or may not be his best film (he also directed 12 Angry Men, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Dog Day Afternoon, Fail-Safe, The Pawnbroker, Serpico, The Verdict, Running on Empty, Prince of the City and Murder on the Orient Express in his distinguished career), but it is right up there, and it may be his most important. I would argue for 12 Angry Men as his most important, but it’s a close call.

Is Network a classic? Absolutely! It’s a brilliant film, ahead of its time, with much to say about the future of television — with much that has already come to pass. It is a hugely entertaining film, acerbic in tone, with wild bursts of absurdity that only confirm it is on the right track. It boasts brilliant acting, especially by William Holden, who did not win the Best Actor prize (Peter Finch did, though he died before the ceremony awarded him the Oscar, making him the first posthumous acting winner). Finch is great, too, as is Faye Dunaway; both of them deserve their Oscars. Beatrice Straight is in the film in two scenes, for just over five minutes; she won the Best Supporting Actress prize and remains the winner with the shortest time on screen. Network‘s fourth Oscar win was for its script, making Paddy Chayefsky the first writer to win three separate times for solo scripts (Woody Allen has since tied that mark). Network earned a total of ten Oscar nominations, winning four. It also won four Golden Globes and several other prestigious awards.

But, let’s face it, some movies win accolades and awards and slowly, or not-so-slowly, fade from view. Network has not faded far from view. It is probably more relevant today than it was when it was made. It is solidly on the Internet Movie Database’s (IMDb) list of the top 250 films of all time. It is a favorite of filmmakers like Paul Thomas Anderson and fans who love their movies a little fiendish and incendiary. While it has dated in some ways it is still prophetic in directions that probably would have horrified Paddy Chayefsky forty years later. It’s an outstanding movie in a Bicentennial year that boasted quite a few outstanding movies. ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆. 17 April 2016.