Featuring a great cast and perhaps the greatest western movie score ever written (by Elmer Bernstein), The Magnificent Seven is a genuine American classic (based, of course, on the Japanese classic Seven Samurai). Like other films that attained classic status, this particular film took time before it was recognized for its qualities. It was not a box office or critical hit in its initial release; only after it gained traction in Europe did it return to American screens and found devoted fans. I’ve always liked it, having come to it years later when it was already established as a classic, and I’ve especially liked that it was first released in the year I was born. In fact, it may be my choice as the best film to premier in the year that I was born (or perhaps second to Psycho).

Appearing near the end of the boon of post-war westerns, The Magnificent Seven takes a decidedly different approach than most other oaters of the era. This “motley group” formula, which would be further popularized in The Professionals, The Dirty Dozen and other action-oriented films, pits a group of skilled, but perhaps less than angelic, men against a foe with even lower morals. The antihero figure was coming into its own in the 1960s and this type of adventure was perfect for framing the ethical uncertainty of the time while still providing a moral cause worth rooting and fighting for. It works because the viewer thinks “even these guys, who have strong reasons to avoid risk and sacrifice, can see that [this particular adventure] is the right thing to do.”

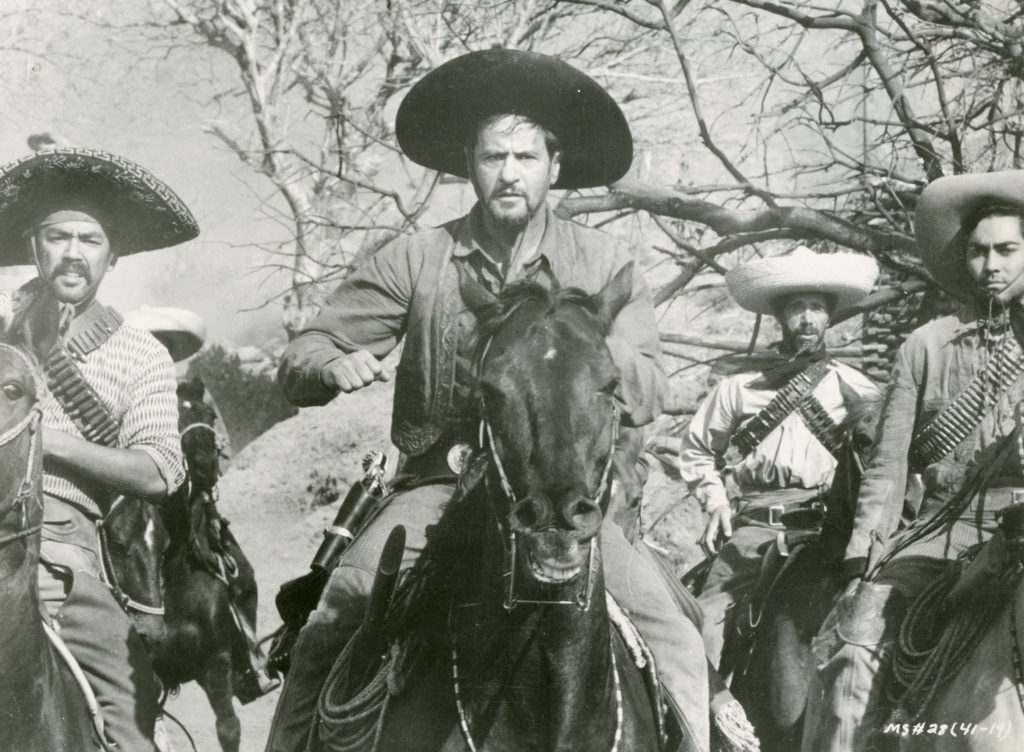

In this case, a trio of villagers approach gunslinger Chris Adams (Yul Brynner), hoping that he will help them buy guns to fight off a bandit named Calvera that is plundering their village. Chris advises them to buy men instead. “Nowadays men are cheaper than guns.” What have they to offer prospective gunmen? All the riches of their village, which figures to be about $20 a man. “I have been offered a lot for my work,” says Chris. “But never everything.” This is what persuades him to help them. And so it begins. Soon, seven mercenaries ride into Mexico to help a poor village of farmers. It isn’t easy. The farmers don’t trust the men completely; they hide their women. Yet the men take their assignment seriously; they teach the farmers how to shoot and defend themselves, and they risk their lives when Calvera (Eli Wallach) and his forty men arrive, successfully driving them away.

Snipers belie the success, and the men hunker down to await the final reckoning. The Seven’s newest and youngest member, Chico (Horst Buchholz; an odd but effective casting choice), reports that Calvera has no plans to leave the area; his men are starving and he needs the village’s meager crops as much as the villagers do. When Calvera makes his move it surprises the Seven; then the dilemma becomes a memorably moral one: to risk their lives for villagers, some of whom have betrayed them — or to ride away, living to fight another foe another day. It is made clear that most such mercenaries would “ride on,” but not these guys. Britt (James Coburn, my favorite actor) says it best. “Nobody throws me my own guns and says run. Nobody.” Six of the Seven head back to the village, and their destiny, with the recalcitrant Harry Luck (Brad Dexter) to make a grand re-entrance to the scene a bit later.

The cast, of course, is tremendous. Yul Brynner and Eli Wallach were the only fully established stars; but Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, James Coburn, Robert Vaughn and Horst Buchholz would all be famous film or television stars within a few years. Only Brad Dexter remains less known by modern audiences, and he made another eighteen movies after this one, through the 1970s. Much of the pleasure in watching this film is watching these guys do their respective things. James Coburn practiced with knives and is outstanding as quiet, lanky Britt. Charles Bronson has never seemed so fatherly. Robert Vaughn is the fearful one, afraid of the demons that he sees in his sleep, yet he displays marvelous moments of courage. The German actor, Horst Buchholz, creatively cast as the Mexican, Chico, simply steals the show several times. Brynner and McQueen are great, especially together in the first sequence, as they drive a hearse up a hill to a local cemetery, getting to know each other a little bit in the face of local opposition to their task. And Eli Wallach is marvelous as Calvera, in another bit of unusual casting.

But the real strength of the film flows from the script. Written by Walter Newman and embellished by William Roberts (who finally got sole screen credit after Newman balked at a shared credit), the film establishes a simple but strong premise, utilizes sparse dialogue to either build or defuse tension, and allows the characters to define the action. I like that the place, the village, ultimately affects most of these mercenaries, as they witness evidence of the lives they might have led. I like that Chico has the temerity to don a sombrero and walk boldly into Calvera’s camp for information. I love that Chico angrily confirm’s Chris’ suspicion that he originally comes from a village very like this one, and that at the end, he returns to his roots. I appreciate that although the villagers’ need is real, and the moral dilemma is an obvious one, that dilemma is seriously questioned during the drama. Not every western is as thoughtful or, frankly, as deep, as this one.

And then there is the music. Elmer Bernstein’s main theme is simply the most recognizable and inspiring western theme ever written. During the 1960s it was hijacked for Marlboro cigarette commercials, and it found a second life in the second film, Return of the Seven (1966). It is one of life’s amazing (and amazingly stupid) facts that there was so little enthusiasm about the film in 1960 that a soundtrack album was not produced. It wasn’t until much later, after a number of instrumental groups had recorded the iconic theme, that a soundtrack album finally appeared. But let me state this for the record (my personal opinion record, of course): Elmer Bernstein’s score for The Magnificent Seven is one of the greatest western scores ever written, certainly in the top ten of all time (I would put in the top three). And his theme is simply the greatest. Period.

Despite a rushed, hectic and helter skelter production schedule (read about that in the prologue to this series), the one-up-man-ship that the entire cast dabbled in throughout the filming and the lackluster reception it received, The Magnificent Seven is one of the greatest westerns ever made. It just is. It has everything going for it, and, other than a deliberate pace, remains just as good today as any other western classic. It is one of my favorites, one which I like even better the more I see it. I highly recommend this movie to anyone and everyone; it is a true classic, and a welcome, worthy successor to the film which inspired it, Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. Even he loved it.

Having said that, the one genuine surprise to be had about this magnificent movie is that it led to a series. I would never have guessed that it would, and I’m not sure that it should have. But six years later, Chris (Yul Brynner) and two other familiar characters (albeit different actors) hit the silver screen again in Return of the Seven (1966). ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆. 15 November 2020.