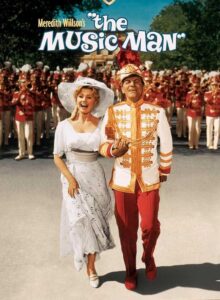

1962 was a great year for movies; this is our second Classic choice in a row having debuted that year. The Music Man opened on Broadway in 1957; it actually beat West Side Story to the Tony award as the Best Musical Play that season. Five years later (one year after West Side Story made Oscar history with eleven wins), the film version found its way to success across America. It’s kind of a wacky story, but one which coalesces into a remarkably effective musical romance, primarily due to the star power of energetic Robert Preston and lovely Shirley Jones, plus the rousing Meredith Willson score.

I didn’t see this movie until I was in college, I think, though I had certainly heard of it and knew some of the songs. I remember not liking the first half very much, and I still don’t. The movie, and its music, doesn’t hit its stride until the “Marian the Librarian” number, but from then on it works its magic and even I am enchanted. When I was young I thought “Seventy-Six Trombones” was its best song; I remember playing that one in band (I played cornet). When I first saw the movie I adored “Marian the Librarian” with its fascinating syncopation, the playful, drawn-out “-ians” of each phrase and the innovative choreography of the library sequence. Now it is the dramatic power of “Till There Was You” that spellbinds me. That is a hallmark of a classic musical — when multiple songs can captivate and enrich the viewing experience. This show has at least four (I include “The Wells Fargo Wagon,” not “Shipoopi”).

Reportedly composer Meredith Willson wrote some forty songs for his original show, eventually employing about seventeen, and perhaps using some of the leftovers for his next project, The Unsinkable Molly Brown. One of the really cool things about Willson’s song score is how two songs share the same melody, yet manage to sound different due to pacing, pitch and accent. “Seventy-Six Trombones” and “Goodbye My Someone” are essentially the same song, but it’s hard to tell until they are combined at the end of the film. The score also counterpoints “Lida Rose” and “Will I Ever Tell You” in a strange manner in which each performance is spotlighted on a different part of the widescreen frame. Most of the other songs are performed traditionally, except for the opening sequence, where “song-speak” is used to establish the film’s story.

That story involves traveling salesman Professor Harold Hill, who specializes in boy’s bands. Hill (Robert Preston) leaves a westward-heading train in River City, Iowa, hoping to find fertile ground to recruit a boy’s band and abscond with the funds for its instruments and uniforms before the residents get wise. Hill finds one friend in River City, Marcellus (Buddy Hackett), a fellow scoundrel who has actually settled into the rural scene pretty comfortably. Hill makes his pitch to the townspeople alerting them to the perils of pool playing children, then offers them a rescue package in the form of a boy’s band. His muckraking works on most of the residents, but not Marian Paroo (Shirley Jones), the local librarian and piano teacher. Nevertheless, Hill persists and is soon a town fixture. He sees the danger that Marian represents, but she tickles his fancy, so he appeals to her young brother, Winthrop (Ronny Howard). Withdrawn since the passing of his father two years earlier, Winthrop is quiet and shy — until he gets his instrument, a shiny new trumpet. When Winthrop shows excitement for the first time in months, Marian’s heart softens a little bit.

Hill also befriends Timmy Everett (Tommy Djilos), a local troublemaker before Hill installs him as his new bandleader. Timmy loves the Mayor’s daughter (Susan Luckey), and Hill promotes their romance, behind the Mayor’s back. The Mayor (Paul Ford) and the School Board (The Buffalo Bills) press Hill for his academic credentials, but Hill continually finds a way of avoiding their requests — a musical way that binds the School Board as nothing previously has done. Hill continues to court Marian, who decides to do some research of her own — only to change her mind as Winthrop blossoms before her eyes. The band forms and learns to play Beethoven’s Minuet in G by using the Professor’s “think method,” humming the tune rather than practicing with their brass instruments. Eventually the uniforms arrive, Hill gathers the money and prepares to slip out of town. But even as Hill is betrayed by another traveling salesman (Harry Hickox), he finds himself unable to leave, having fallen in love with Marian and grown attached to her precocious brother. This leads to a memorable musical recital and the crescendo-of-marching-music finale of “Seventy-Six Trombones.”

Realistic, it isn’t. But effective, it is. Robert Preston repeats his Tony-award winning performance in the film, and he is perfectly cast. Cary Grant was offered the part, to which he reportedly replied “Not only will I not star in it, if Robert Preston does not star in it, I will not see it.” Even though he had been sporadically starring in films since the late 1940s Preston was not considered a major star; Warner Bros. finally agreed to give him the part and everybody was happy. That happy ending did not extend to Barbara Cook, who played Marian on Broadway and won a Tony for her effort. The studio insisted on a film star in the part and recruited Shirley Jones, who was a terrific choice. Cook continued to star on Broadway, was nominated for another Tony award fifty-two years later, but never appeared in a feature film. It’s sad for Cook, but casting Shirley Jones cannot be faulted; Marian is one of her iconic roles, cementing her status as one of the great musical movie actresses.

Morton DaCosta, who had directed the stage play, helmed the film hoping to open it up a bit, filming in widescreen and filling that screen with as many dancers and townspeople as he could realistically fill it. Big-scale sequences are staged in the town square, the high school gymnasium and the local park. But DaCosta knew how to keep the dramatic focus on his main characters and does so in interesting ways. Note that Harold Hill has one line early in the “Rock Island” train segment at the beginning of the story and then disappears until it is time to reveal himself. Or how Marian sings “Being in Love” at the windowsill with Amaryllis in the background, seen largely from outside. And he veers into pure fantasy for a few shots, whether it is the Biddys being seen as chickens or the band as Harold Hill sees it in his imagination (and at the finale). The one segment that seems peculiar is the “Lida Rose / Will I Ever Tell You” counterpoint that switches spotlighted segments on a darkened screen. I’m not sure what he was going for with that; it seems forced and arbitrary.

Unlike virtually any other musical I can recall, all of the best songs feature in the second half of the story. I mentioned before that I don’t really care for the first half; that is due to the heavy stylization of the opening number, the fact that Harold Hill is introduced as a despicable con man and the weirdness of the Iowa population, not to mention all the fuss about a pool table (I like to play, myself). But once we get to the “Marian the Librarian” number, the tide turns. That song, and its choreography, is so cool that it wins me over every time. And once Marian begins to fall for Harold Hill, it becomes impossible to hate the guy. His kindnesses to Winthrop and Timmy Everett go a long way to make him more palatable, too, but it is Marian’s devotion to him, protecting him from the Mayor and the School Board, not caring about his past as long as he does the right thing in the present, that redeems him. And he earns that redemption (although the film lets him off the hook far too easily, I think, at the finale).

Anyway, the second half features “Marian the Librarian,” “The Wells Fargo Wagon,” “Till There Was You” and “Seventy-Six Trombones,” all of which are, in my opinion, classic movie songs. And “Being in Love” and even “Gary, Indiana” and “Shipoopi” are at least decent. I’ve always felt that many musicals, even the great ones, pack all their best songs into the first half. That is certainly the case with Fiddler on the Roof, for instance; that last hour is pretty dry. But not this one. The music gets better the longer it goes. “Till There Was You” has become my favorite song in the film; I find it incredibly powerful now. And I will always have a soft spot for the big finale since I used to play “Seventy-Six Trombones” on my cornet, possibly (I cannot recall for sure) in my school’s marching band. The film makes it look easy, but let me tell you from experience, playing an instrument while marching in unison is not an easy task, especially for one as uncoordinated as myself. I grew to despise parades because I marched in so many of them (and it may not have been all that many, but it sure seemed so).

The Music Man premiered in June of 1962 and was a big hit, probably more so than Warner Bros. expected. It made $8 million, ranked as the seventh highest-grossing film of the year, and the only Warner Bros. title in the top ten. It was nominated for six Academy Awards, including Best Picture and won one, for Music — Scoring of Music, Adaptation or Treatment for Ray Heindorf’s orchestrations. It also won the Golden Globe as the Best Comedy / Musical of the year. And the film was added to the National Film Registry in 2005. It was remade as a 2003 TV-movie with Matthew Broderick and Kristin Chenoweth, following Broderick’s successful Broadway run a bit earlier. And the stage play is a popular revival, currently on Broadway with Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster as the leads.

Is The Music Man a classic? You betcha. The music makes it so; those four songs are evergreen favorites that have lasted decades in the popular culture (“Saturday Night Live” recently did their own take on “The Wells Fargo Wagon,” but that’s a wholly different discussion). Robert Preston and Shirley Jones are iconic in their roles and the whole thing (after a rocky start) is delightful. It’s a bit old-fashioned and quirky but this movie stands up as a classic musical, and not just of its era. I like it a whole lot more than either Gigi or An American in Paris, both of which won Best Picture Oscars. I think it’s better than either of those, or both combined. A year later it might have won even more accolades, but 1962 was the year of Lawrence of Arabia, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Miracle Worker, The Longest Day and many other classics. That it stands out even among those titles is a tribute to its enduring popularity. Watch it and enjoy it; its exuberance is infectious. ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 30 December 2022.