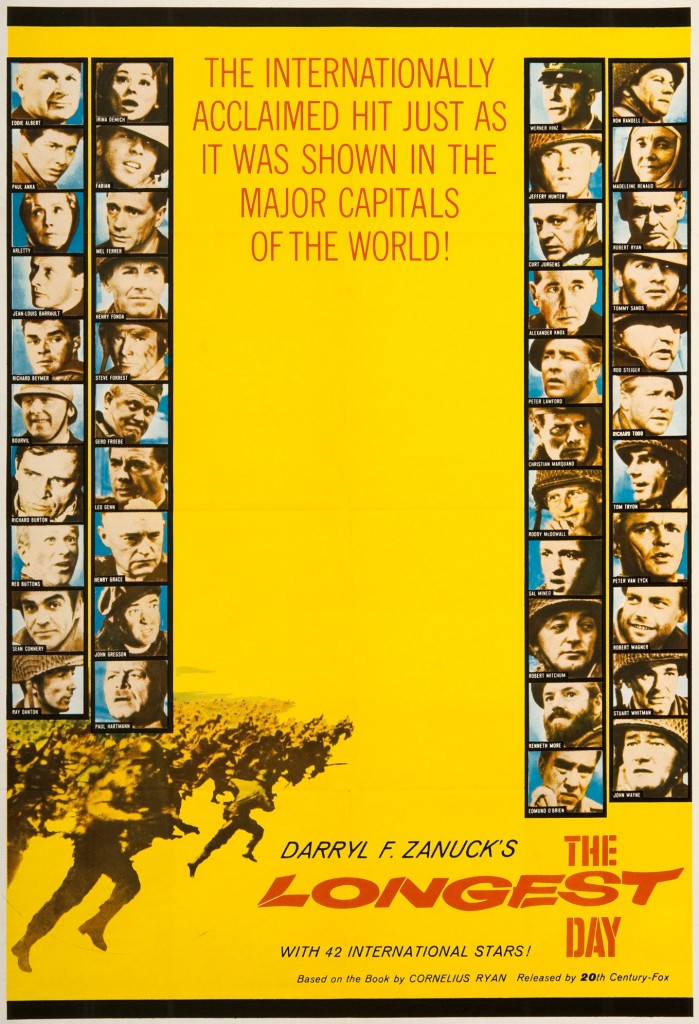

Our seventh classic of 2014 is producer Darryl F. Zanuck’s epic retelling of the World War II D-Day invasion, The Longest Day. At the time it was made, this film was one of the most expensive productions ever put together, and unfortunately for 20th Century-Fox that studio was also making a little historical potboiler named Cleopatra. The costs and scale of both films being made concurrently came close to bankrupting the studio. However, The Longest Day was released to great acclaim and popularity, becoming the highest-grossing black and white film ever released, until Schindler’s List caught and passed it in 1993-94. In 1963 Cleopatra also grossed a ton of money, but it had cost so much to make that it still lost money for the studio.

Our seventh classic of 2014 is producer Darryl F. Zanuck’s epic retelling of the World War II D-Day invasion, The Longest Day. At the time it was made, this film was one of the most expensive productions ever put together, and unfortunately for 20th Century-Fox that studio was also making a little historical potboiler named Cleopatra. The costs and scale of both films being made concurrently came close to bankrupting the studio. However, The Longest Day was released to great acclaim and popularity, becoming the highest-grossing black and white film ever released, until Schindler’s List caught and passed it in 1993-94. In 1963 Cleopatra also grossed a ton of money, but it had cost so much to make that it still lost money for the studio.

Based on Cornelius Ryan’s bestselling chronicle of the events leading up to D-Day (the sixth of June in 1944) the mammoth three-hour film sets the stage by depicting the preparations of the Allies, the occupation of France by the Germans and their rather nonchalant defensive strategies along the Normandy coast. The Germans remained convinced that the Allies would attack at the shortest distance across the English Channel, at Calais, which is exactly why it did not happen there. The film takes nearly an hour to set the stage for the various phases of the operation, before it finally launches into action.

Zanuck made a trio of important decisions before production began. First, to film in black and white rather than color. Most images of World War II were photographed in black and white, and he believed that the film needed to reflect the way most people remembered the war. Second, that the movie would, like the book, encompass a grand scale of the invasion, with dozens of characters in brief scenes. To get the most impact Zanuck decided to cast stars in virtually every major role. This boosted the budget, but also heightened the project’s public visibility and made each character more memorable. Third, in order to tell the story as objectively as possible, he hired three main directors and assigned them different viewpoints. Andrew Marton (who was supervised closely by Zanuck) handled scenes with Americans; Ken Annakin handled scenes with the British and French; and Bernhard Wicki handled scenes with Germans. The film was then edited seamlessly into one wide-ranging overview of that fateful day in history. Zanuck also recorded the French dialogue in French and the German dialogue in German, which was unusual for American films of that era. Note the way the letterboxing is raised so that subtitles can be placed in the larger black area at the bottom of the screen; it is an ingenious way to present translated dialogue without sacrificing any of the visual composition.

Zanuck arranged for more than twenty thousand troops from the U.S., Britain and France to take part in the film (some of them as Germans), along with tanks, boats, airplanes and all manner of military gear to provide verisimilitude. This would become the definitive D-Day invasion film until Steven Spielberg came along with Saving Private Ryan in 1998, which dramatically changed the way battle scenes are filmed. Much of Saving Private Ryan takes place on Omaha Beach, but then it moves on to further events of the war. The Longest Day targets the Normandie area for the majority of its 178 minutes, demonstrating how the beaches were stormed by men from the sea, how inland towns were infiltrated by men from the air and how the Allied push was aided by French resistance fighters, all of whom fought bravely and many of whom suffered and died during that singular moment of history.

With its forty-two international stars, the film pinpoints individual stories among the thousands of participants and utilizes them to illustrate various important moments, personalities and themes. For instance, soldier Richard Beymer wins big at craps while waiting for the action to start, then reconsiders as he thinks about the nature of luck. He spends the next few hours trying to “clean” himself before going into battle. Another soldier, Sal Mineo, learns the hard way that the “clicking” technique taught to everyone for identification has one big flaw.

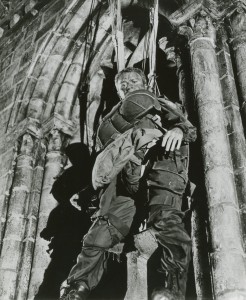

Most poignantly, parachutist Red Buttons and his comrades drift past their drop zone right into the middle of hostile territory. Buttons is forced by circumstance to hang and watch his fellow parachutists become easy targets for the Germans below as they float to the ground. He doesn’t dare make a sound for fear of his own life, and he cannot attack the enemy from his lofty perch. It’s an incredible scene that is chillingly tragic.

Unlike the plethora of propaganda-filled war adventures made during the war and soon afterward, The Longest Day offers audiences a balanced view of history. American and Allied mistakes are acknowledged; German arrogance causes confusion and delay. The Fuhrer sleeps while Normandy is invaded and the reserve Panzer tanks never move into position. The Americans parachute rubber dummies (“Rupert”) with firecrackers into specific areas to distract attention away from their actual landing spots. Only two German planes are left to defend the Normandy coast, and they strafe the beach just once before fleeing to inland safety. A British unit marches into battle led by their bagpipes player. French citizens celebrate as the invasion begins, even as their homeland is ground into dust by artillery. Soldiers and officers on all sides wonder if it is all worth it.

The Longest Day has a little bit of everything, but succeeds because it emphasizes scope, humor and heart. The first hour teaches us the situation as seen from both sides of the conflict, and how the Allies were able to fool the Germans until the very moment arrived. Zanuck and his directors visually stress quantity whenever possible, from the huge billet filled with men waiting to fight to the awesome shot of ships heading toward the Normandy beach. Sometimes it’s both intimate and epic, as in the brilliant point-of-view shots from the German planes as they strafe the beach.

The movie’s best shot is probably in Ouistreham as Commander Phillipe Kieffer (Christian Marquand) leads the French commandos into town. As the commandos rush from building to building, the camera rises on a helicopter to follow them for a couple of minutes, aerially framing their marathon sprint through the town and across a river to the German headquarters in a former casino. It’s a breathtaking shot that reduces the human element but reinforces the picture of war as mass advancement against force.

Humor is present but rarely forced. Some figures are more comic than others, such as Captain Colin Maud (Kenneth More), who takes his bulldog Winston onto the beach and uses his swagger stick to batter recalcitrant engines into obedience. Two Irish soldiers (Norman Rossington and Sean Connery) assume the traditional role of the complaining dogface, dryly commenting on various aspects of the operation as they gradually move inland. The French mayor (Bourvil) is so thrilled that he meets the soldiers on the beach, offering them champagne as the bullets fly. Richard Beymer is the only American soldier who notices that the soldiers who pass by on the other side of a short stone wall are of German descent. Messages cannot be sent so pigeons are utilized; naturally, they fly inland instead of across the English channel. And, of course, much of the dialogue is comprised of the good-natured grumbling that has populated every war film since the advent of sound.