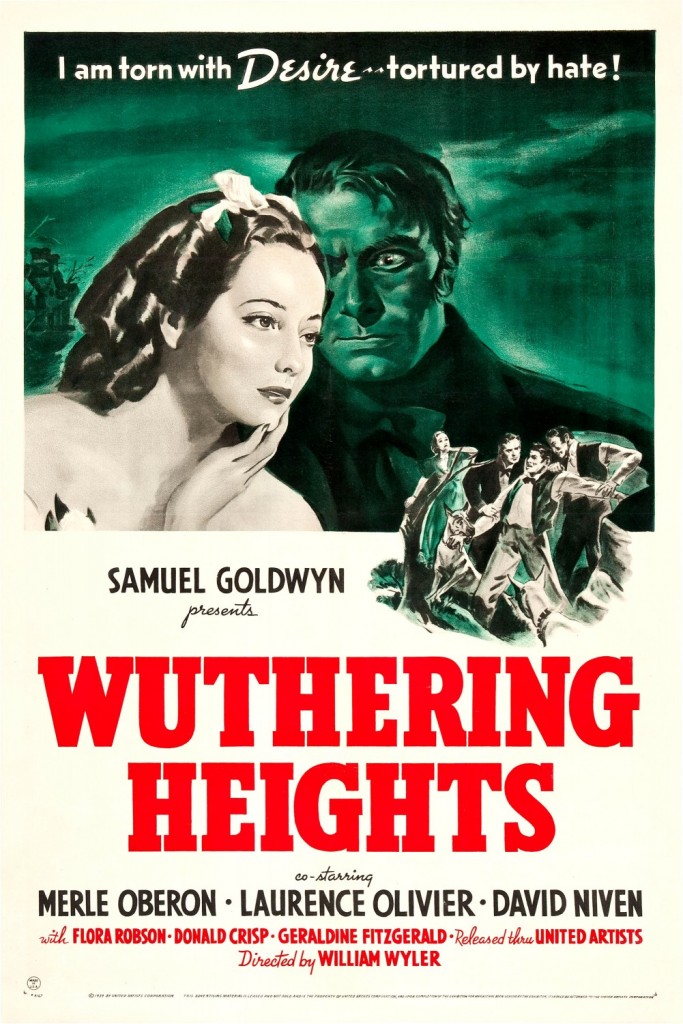

Our first potential classic of 2015 is another one of 1939’s Best Picture nominees: William Wyler’s romantic melodrama (produced by Samuel Goldwyn, who often claimed the movie as his own) Wuthering Heights, which was based upon the first sixteen chapters of Emily Brontés famous novel. I’ve never liked the title, as I’ve never heard the word “wuthering” used in any other context except in this title. But it fits; “wuther” is a British verb meaning a fierce wind, which is certainly appropriate to the story, and probably to the production as well, which was notoriously stormy.

romantic melodrama (produced by Samuel Goldwyn, who often claimed the movie as his own) Wuthering Heights, which was based upon the first sixteen chapters of Emily Brontés famous novel. I’ve never liked the title, as I’ve never heard the word “wuthering” used in any other context except in this title. But it fits; “wuther” is a British verb meaning a fierce wind, which is certainly appropriate to the story, and probably to the production as well, which was notoriously stormy.

Director Wyler convinced independent producer Goldwyn to tackle the project, as he was convinced that the tragic tale of Heathcliff and Cathy’s romantic love would make a great movie, and that the detail-oriented Goldwyn was the right man to make it. Emily Bronté’s tale of a love dictated and divided by social strata and class differences was one of the major literary works that had not yet been filmed as a major production. Goldwyn didn’t like the idea of his protagonists dying, but Wyler was firm about it. Goldwyn sort of double-crossed the director by adding the ghostly epilogue that concludes the movie, providing a modicum of a happy ending, after Wyler refused to film the sequence himself. The result is one of the most highly regarded romantic tragedies in Hollywood history.

In 1841 England (switched from the late 1700s England by scriptwriters Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur), Mr. Earnshaw (Cecil Kellaway) surprises his family by returning from a trip with a young gypsy vagabond, Heathcliff. Earnshaw accepts Heathcliff into the family, as does his young daughter Cathy, but his son Hindley resents the intruder. Cathy and Heathcliff form a powerful friendship, which is put to the test as soon as Earnshaw dies. Hindley (Hugh Williams) inherits their estate, Wuthering Heights, and forces teenaged Heathcliff (Laurence Olivier) to the position of stable boy. Cathy (Merle Oberon) continues to profess her love for Heathcliff, but she also wants a life of luxury and beauty, which he can obviously not provide.

Cathy becomes infatuated with the upper-class Linton family, especially the son, Edgar (David Niven), who is just as infatuated with her beauty. Cathy becomes torn between the lively social vagaries at the Linton estate and the love of her life, stuck as a lowly stable boy at her own dour estate. A fight between them sends Heathcliff away, seemingly for good, allowing Cathy to seal her fate with Edgar Linton.

But lo and behold, Heathcliff makes a fortune and returns to Wuthering Heights, gaining its title by paying off Hindley’s excessive gambling debts. And instead of throwing him out once and for all, Heathcliff orders Cathy’s drunken brother to stay, psychologically mired for good in the one place that makes him miserable. Wuthering Heights — which rarely seemed a happy home — becomes almost dungeon-like for its inhabitants, even when Heathcliff marries Edgar Linton’s fun-loving sister Isabella (Geraldine Fitzgerald). Cathy becomes ill (again), which prompts Heathcliff to visit the Linton estate and declare his love for her again; she finally admits her love for him and dies in his arms. Some time later, Heathcliff is found dead on the moors, alone, after having been seen with the ghostly Cathy.

The gothic atmosphere of Wuthering Heights is palpable, due primarily to Gregg Toland’s marvelous Oscar-winning black and white cinematography. The mystical, poetical power of Peniston Crag is made real and vibrant, a perfect rendezvous for two people whose love can never be consummated but yet will never be denied. It is there, on the windy moors, where the elemental Heathcliff is Cathy’s soulmate, which even she recognizes. She loves the moors, but she also loves the warmth and light of social occasions in fancy locations, and she is unable to choose one over another until fate forces her hand.

Heathcliff is brooding, enigmatic, cruel and yet completely believable because he allows his emotions to rule him — until he forces himself to subjugate everything in his being to making a fortune, for Cathy’s sake. But Cathy doesn’t wait for him, and because he won’t let her go, only bitter tragedy awaits him. He is played with dashing ferocity by Laurence Olivier, who scored the first of his ten Academy Award nominations for his performance. Olivier did not want the role and did not want to leave wife Vivien Leigh in England while he filmed in California, but he reluctantly acquiesced. He battled with director Wyler about his acting, but finally came to realize that direction was just what he needed to become a better film actor. Olivier’s portrayal of Heathcliff provides the film with its fundamental power, and this role provided the momentum which made the Shakespearean actor the most highly acclaimed film actor of his generation. Although he had been making movies since 1930, it is this one that truly made him a movie star. This is true even though Wuthering Heights failed to recoup its rather large budget until a 1950 re-release. And while this title has been filmed several times over the years, the critical consensus is that there has been no better Heathcliff than Laurence Olivier.

Cathy, on the other hand, is a brat. She has Heathcliff’s devotion, but it isn’t enough for her. She wants all the pretty things that her existence at Wuthering Heights does not provide. She wants the adulation of other, socially acceptable men, and is willing to trade that for Heathcliff’s love. As a literary character Cathy is a wellspring of feelings and emotions and contrary action; as a film character she seems flighty and insipid. Merle Oberon was an established actress with a 1935 Oscar nomination under her tiara when MGM cast her as Cathy, and a legion of classic film fans love her performance, but I find it rather superficial. Cathy’s romantic conundrum should be earth-shattering within her close social circle, yet her flutterings between Edgar Linton and Heathcliff barely raise eyebrows. Perhaps it is the fault of the script, but I think Merle Oberon’s characterization is rather colorless.

That is not the case for Isabella Linton (Geraldine Fitzgerald). Edgar’s sister is beautifully brought to vibrant life before having her happiness squashed flat by moving to morbid Wuthering Heights as Heathcliff’s wife. Isabella’s plight is far more involving and heartrending than Cathy’s, at least to me. Where Cathy is foolishly coquettish Isabella is naïve, yet real in ways that Cathy is not. It isn’t a great difference, but it’s strong enough to shift the dramatic balance of the film for me. Fitzgerald was nominated for a Supporting Actress Oscar for her work; it is worth mentioning that Merle Oberon was not (in a crowded 1939 field).

A third important woman frames the story. Housekeeper Ellen Dean (Flora Robson) tells a wandering traveler (Miles Mander) who arrives at Wuthering Heights on a stormy night the tragic romance that has cursed the estate for years. Most of the movie is told in flashback fashion by Ellen, who has been in the background at Wuthering Heights since Heathcliff arrived from Liverpool with Mr. Earnshaw. Ellen tells the story with a compassion for Cathy and Heathcliff that helps endear them to us, and to the wandering traveler, quite effectively.

The social distinctions that separate Cathy from Heathcliff are imperative to the story, but seem terribly old-fashioned to modern viewers. The film does a nice job of illustrating just how different things were back then, and why, and how characters coped with those differences — or did not cope. But ultimately I feel the film’s overriding themes involve the differences between men and women. At Peniston Crag Heathcliff and Cathy love each other and want the same things. But at home or in social settings, their desires become incompatible. Cathy wants social significance with all the trimmings, and she feels, or knows, that she cannot have them with Heathcliff. All Heathcliff wants is her continued devotion, and respect. Heathcliff eventually realizes that he will have to earn that respect by making his fortune, so he does. But that doesn’t help him to win her devotion, and it turns him into an unfeeling cad. Cathy, meanwhile, feels everything so deeply that her very health is affected. Cathy’s life is ruled by her feelings, and she has so many of them that she cannot settle on the ones that would make her happy. The men in the film have no such quandaries.

This is a beautiful example of the adage “they don’t make ’em like they used to.” No, they don’t, not like this. Wuthering Heights is a beautifully crafted film which brings half of an acclaimed literary novel to spirited life. It features indelible acting, terrific production values and very welcome literary sophistication. The 1930s and ’40s saw a great many beacons of literature transferred onto celluloid with wild success, and this property is one of them. Many viewers consider it a masterpiece, although I suspect that number is dwindling as we move farther away from the social scenario that it evokes.

Is Wuthering Heights a classic? Yes. It isn’t really my type of movie, so it’s hard for me to be as enthusiastic as it may deserve. I still have doubts regarding Merle Oberon’s performance; I like it, but I don’t believe it is great. Olivier, on the other hand, is great. So is Geraldine Fitzgerald, and Flora Robson. The ghostly epilogue added by producer Samuel Goldwyn is absolutely the right touch. While the film had more than its share of production problems and dust-ups among the cast and crew, it’s amazing to me to think that this movie which absolutely oozes British charm, gloom and doom, was produced and filmed in sunny southern California. In many years Wuthering Heights would be an Oscar front-runner; in 1939 it garnered eight nominations and won just once, for Gregg Toland’s magnificent cinematography. Yet it is a movie that has not only survived but remains well-remembered and regarded today. It is certainly a classic. ☆ ☆ ☆ 1/2. 1 March 2015.