For this issue I have decided to spotlight two seminal soundtracks by the late, great Henry Mancini. In the late fifties / early sixties, he was The Man for creating hip, melodic, popular film soundtracks. Weaned on Universal product throughout the ’50s under the tutelage of Hans Salter and Herman Stein, Mancini wrote or contributed to the scores for and orchestrated dozens of films during that time, mostly uncredited. His big band experience proved invaluable and his penchant for big band jazz landed him the gig for scoring TV’s “Peter Gunn” and Orson Welles’ film Touch of Evil (1958).

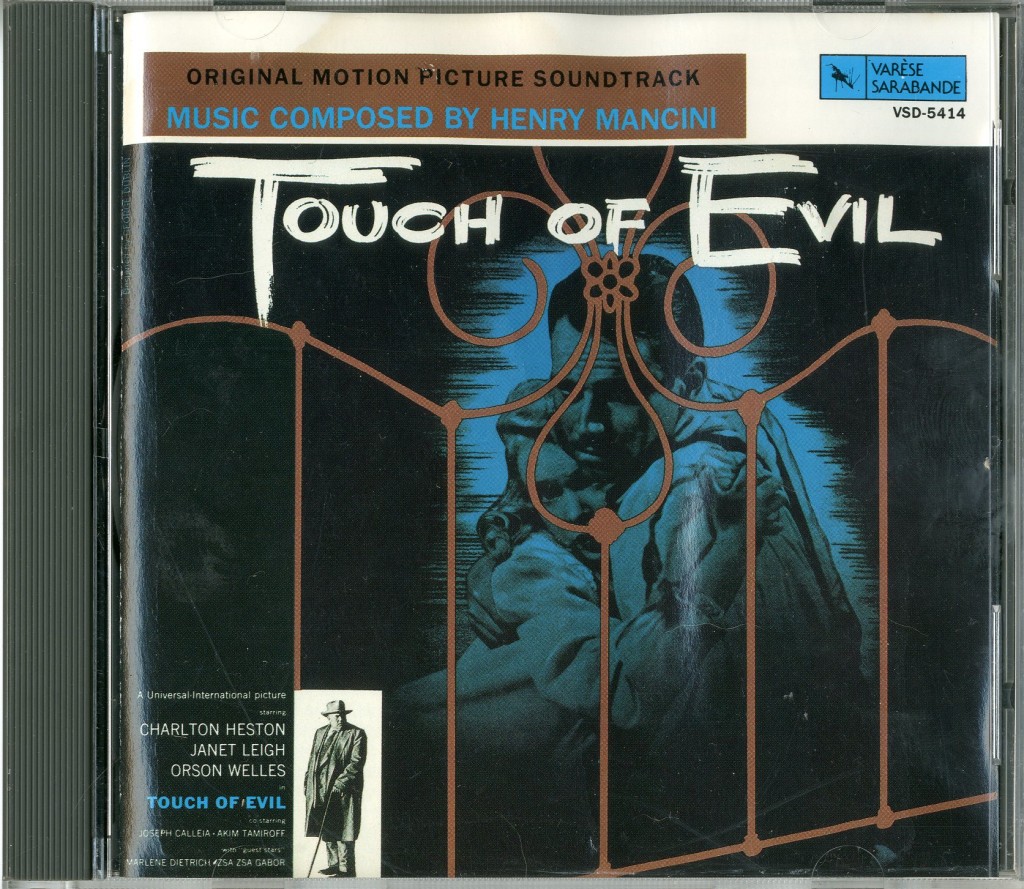

Had Touch of Evil been a prestigious project, Mancini would in all likelihood not have received the assignment. But as Orson Welles took over and turned a B-movie into a minor masterpiece, Mancini rose to the challenge, contributing a moody, jazzy score that enhances the action as surely as Welles’ direction improves the film. Mancini’s score is Elmer Bernstein-like, but with more melody and reliance on rhythm and syncopation. A preponderance of bongo drums and brass is heard early and often, yet they do not overshadow the score’s more nuanced passages.

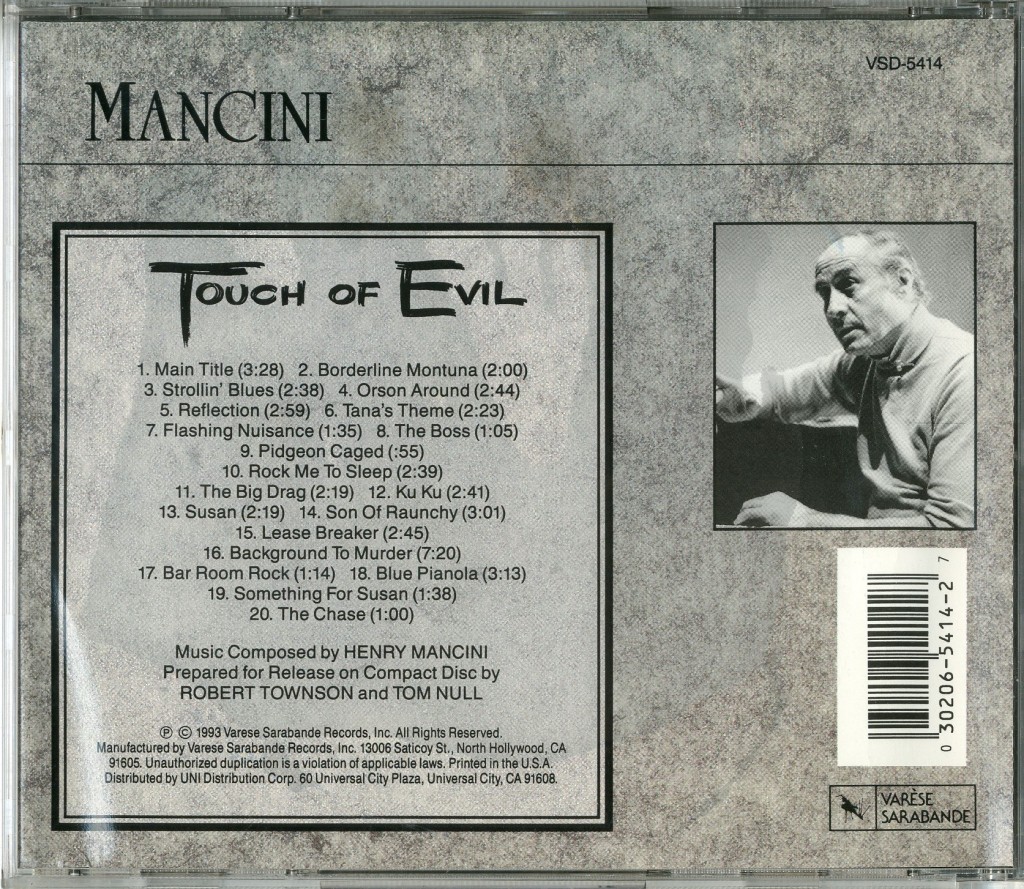

The “Main Title” begins darkly, then moves into a sweeter sound with trumpets, saxophones and bongos mixing melody, harmony and a noirish atmosphere while we wait for the bomb that was planted in the car at the beginning of the most famous extended shot in cinema history to explode. “Borderline Montuna” is the opposite; it starts sweetly and then bursts into jazz fusion with a galloping trumpet solo and an intense climax.

Welles dictated that Mancini’s music should sound as if it was coming from radios and other sources, so the score offers several “Afro-Cuban rhythm numbers,” as the director referred to them. Using electric guitars and a minimum of instruments, Mancini turned tracks like “Strollin’ Blues,” “Orson Around,” “Rock Me to Sleep,” “The Big Drag,” “Ku Ku,” “Son of Raunchy” and “Bar Room Rock” into numbers you might hear at a jazz-oriented sock hop. “Lease Breaker” is a bit more ambitious but in the same vein. However, other cuts like “Flashing Nuisance,” “The Boss,” “Something for Susan” and “The Chase” continue to emphasize the danger that awaits cop Charlton Heston as he investigates corruption on the Mexican side of the border.

Two tracks are really striking. “Background to Murder” is a seven-minute recap, extrapolation and reconstruction of the main theme with a gradual crescendo that evolves into a semi-discordant, free-form fulmination of sound as it accompanies the murder of Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff) in a darkened bedroom. The other is my favorite cut of the album: a slow, smooth ballad called “Susan,” with a bouncy bass line and with a melody played skillfully on piano, xylophone and guitar. The more I hear this track, the more I like it. But that’s true of the entire album, a Mancini classic.

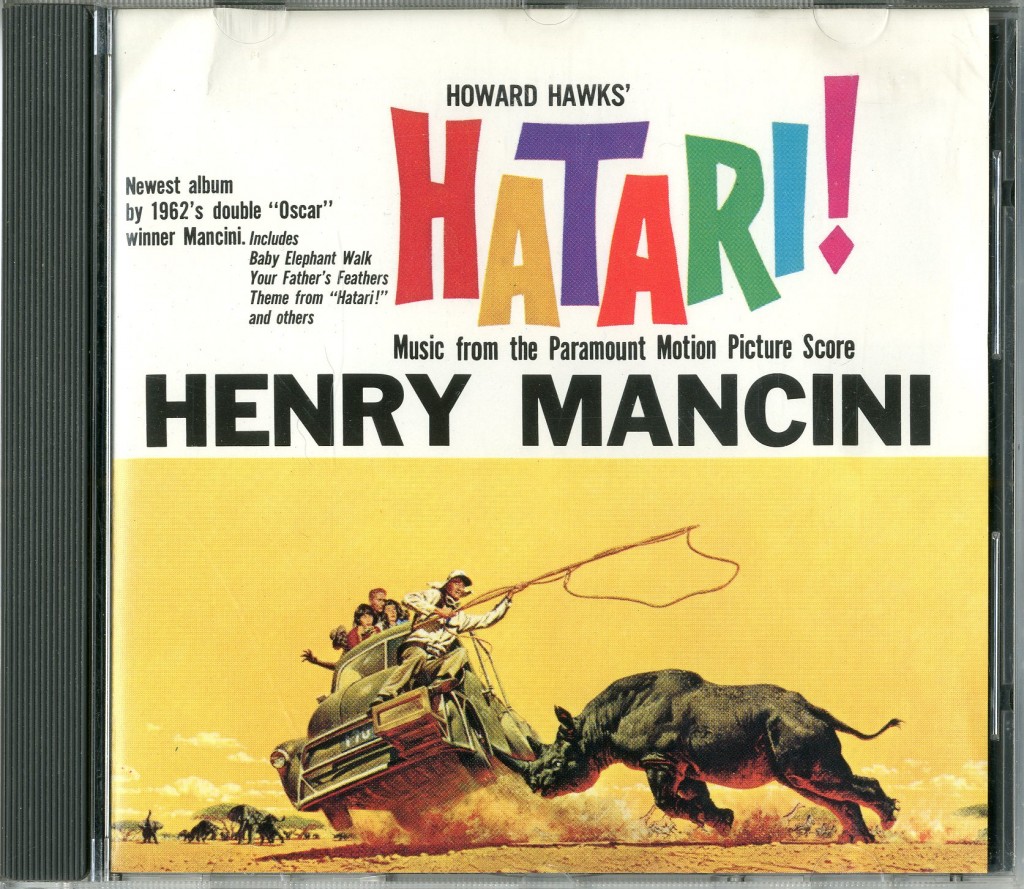

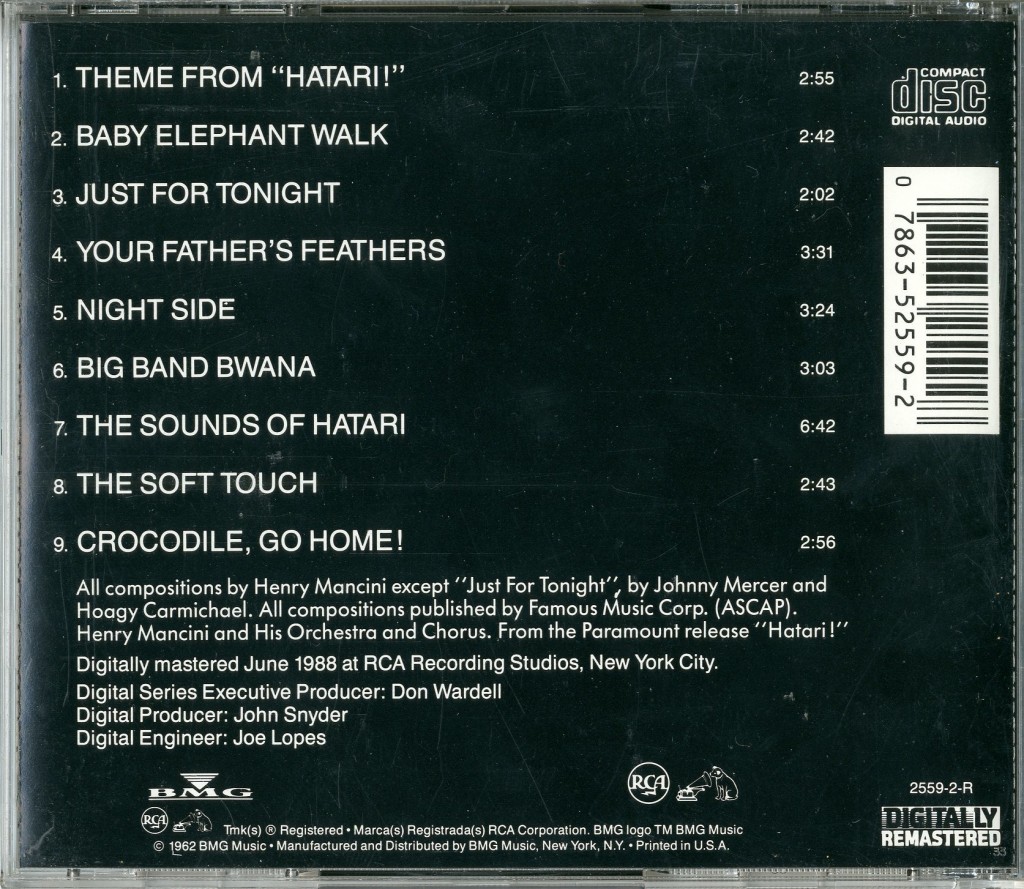

More mainstream is Mancini’s largely comic score to Hatari! (1962), a largely comic movie. One track in particular, “Baby Elephant Walk,” with its catchy melody and unusual instrumentation (clarinets and flutes to represent the elephants) was a worldwide hit and remains one of Mancini’s most recognizable musical motifs. Just about as catchy and enjoyable is “Your Father’s Feathers,” played while John Wayne, Hardy Kruger, Red Buttons and company chase some ostriches around their African camp. Other cuts such as “Big Band Bwana” and “Crocodile, Go Home!” prove that nobody was as adept at moving between and combining easy listening sounds, jazz riffs and big band orchestrations as Henry Mancini. Ever.

I love the movie Hatari! and a prime factor is its music. Aside from the brilliant, unforgettable “Baby Elephant Walk,” my favorite cuts are not, however, from the comic side of the film. The main “Theme from Hatari!” and “The Sounds of Hatari!” are the tracks I love the most, especially the latter. The main theme is somewhat sad yet exhilarating, promising adventure and excitement. “The Sounds of Hatari!” is almost entirely percussion for a while, adding rhythmic bass notes on beats 5 and 8 of the measure and gradually increasing the tempo until the drumming sounds like a herd of wild animals charging at the speakers. It’s just what the movie calls for, which is the sound that great composers deliver. Henry Mancini was a master. (10:3).