This article, and those that follow, initially appeared in Filmbobbery, Volume 9, Issue 1 (Summer, 2007). That should explain any references to other pages and articles.

With the recent success of Nancy Drew this summer (my review of it is on page 14), I feel that this is a prime opportunity to revisit the first cinematic incarnation of the character. In 1938 and 1939, a brief series of four movies were produced by Warner Bros., starring Bonita Granville as the teenaged sleuth. These are the films which will be under discussion, but let’s first examine the history of the famous female super snoop.

“Nancy Drew” began as an idea by publisher Edward Stratemeyer, a relatively unknown figure even today who, by operating a publishing syndicate as a producer would run a movie studio, found a way to mass produce literary entertainment and make a fortune. Under various guises and pseudonyms, Stratemeyer originated dozens of series, writing outlines for their basic stories and farming out the actual writing assignments to writers eager for a steady paycheck and willing to forego rights to the material they were creating.

The Stratemeyer Syndicate founded such popular dime novel series characters as the Rover Boys, Dorothy Dale, the Bobbsey Twins, the Motor Boys (and the Motor Girls), Ruth Fielding, Tom Swift, the Blythe Girls, Baseball Joe, the Outdoor Girls, Bomba the Jungle Boy, the Hardy Boys, the Motion Picture Girls, and Nancy Drew. All of these and more were aimed at the teen market in both content and form, were priced affordably and were churned out in ever-increasing numbers. But Edward Stratemeyer died of pneumonia on May 10, 1930, just two weeks after the first Nancy Drew volume was published.

Although Stratemeyer conceived the first five Nancy Drew stories on his own and edited the first three before his untimely death, he did not write those stories. As was his custom, he found freelance writers and cultivated them for his specific assignments. For Nancy Drew (who was originally known as Stella Strong until publishers Grosset & Dunlap chose Nancy Drew as an alternative), Stratemeyer chose a writer named Mildred Wirt.

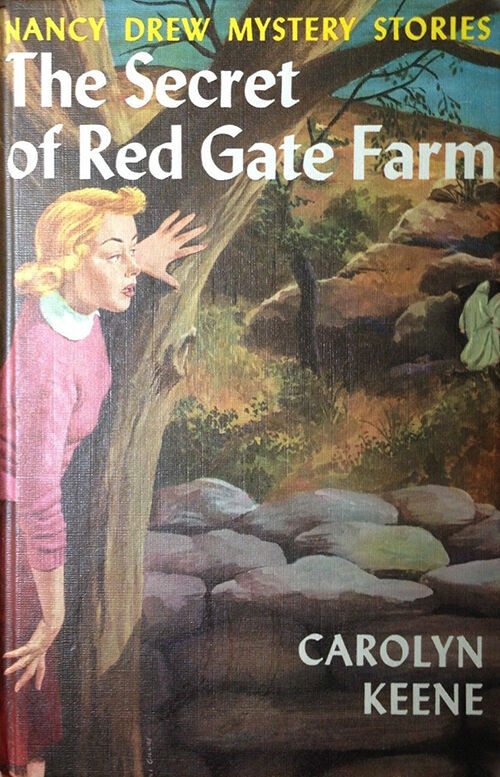

Mildred Wirt was the first author to assume the nom de plume of Carolyn Keene, the pseudonym chosen by Stratemeyer for the Nancy Drew series. She, and all of the other writers in the Syndicate, were forbidden to publicly reveal their work in bringing the Syndicate’s novels to print.

Stratemeyer’s death threatened to end the activities of his Syndicate, until one of his grown daughters, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, agreed to take over the company on an interim basis. That interim lasted half a century, and after Mildred Wirt’s term of Nancy Drew’s primary author ended (23 books), Harriet Stratemeyer Adams took over the series. Due to changing times, fads and fashions, the original Nancy Drew stories were also rewritten by Adams during the 1960s. So if you have a copy of one of the early works, you might want to compare it to the same story published in 1959 or later; there will be noticeable (sometimes resounding) differences.

Even through decades of change and turmoil, Nancy Drew has remained a steadfast bastion of intelligent young femininity: attractive yet innocent, smart yet humble, witty yet not mean-spirited, charming yet stubborn, materialistic yet simple, curious to a fault yet tough enough to take care of herself. During the Great Depression Nancy Drew provided uplifting, escapist entertainment; during World War II her adventure became patriotic; the post-war years found her increasingly cosmopolitan and worldly. The revisions made to the series in the 1960s brought Nancy Drew into the modern era but in doing so also homogenized her personality; the later Nancy is not so much a non-conforming, obsessive young woman as a smart, pretty, curious girl to whom crazy and dangerous things happen.

Still, the Nancy Drew books are often cited by women as an important factor in their maturation. The character was one of the first, as written by Mildred Wirt, to openly (but charmingly) flaunt convention and establish a woman’s right to expect and enjoy the freedom to do whatever she wished. Nancy Drew’s sleuthing brings her into contact and competition with assorted villains, whom she regularly outwits. By using her brains — and not her sexuality — she not only solves crimes and mysteries but also improves the lives of those around her.

From the very beginning, Wirt saw her heroine as more than just a cookie cutter character. Wirt developed Nancy’s acumen, taste and charm into a full-blooded characterization more memorable for her personality and style than her adventures. While most of the other juvenile literary series of the era have passed into distant memory, Nancy Drew has not. Her escapades are read and re-read today, whether in their original form, revised editions, or recently published adventures set in contemporary times.

It seemed only natural that Nancy Drew would one day find her way to the big screen. In 1938 Warner Bros. paid the Statemeyer Syndicate the lofty sum of $6000 for the rights to make a series of Nancy Drew movies. Warner Bros. was looking for a franchise that would rival the one just begun at MGM, Mickey Rooney’s Andy Hardy series, which was proving that features about teens were not only profitable but had the potential to be immensely popular. The studio spent the money to obtain the rights, and then did what studios often did to properties they acquired: they changed almost everything about the project which initially appealed to them.

Golden-tressed Nancy tooling around town in her blue roadster (blue is her signature color) would have wowed ’em in Technicolor. So, naturally, the studio filmed in black and white. Fully developing Nancy’s circle of friends might have provided the depth necessary to build her stories into a franchise and keep it running for years. Instead, Warner Bros. eliminated Nancy’s best friends Bess Marvin and George Fayne entirely, altered Ned Nickerson’s name to Ted Nickerson because Ted was a more popular name, chopped the budgets for the anticipated films to the B-level and insisted on running times no longer than seventy minutes. The studio eschewed its brighter directorial lights in favor of William Clemens, a former editor whose career never rose past helming series entries of Philo Vance, the Falcon, Perry Mason, Torchy Blane . . . and Nancy Drew.

Even the source material is wasted. The first films of the series, Nancy Drew — Detective (1938), is just slightly based on “The Password to Larkspur Lane.” The second and third movies are new stories entirely, while only the fourth and final entry shares its title with a Nancy Drew novel — “Nancy Drew and the Hidden Staircase.” Further, the changes to Nancy herself during the movies threaten to blur the literary image of the energetic crime solver. In the second movie, her goal is to become a reporter! The third and fourth films turn the smart and resourceful Nancy into — at times — a whiny scaredy cat.

Yet even though the four Warner Bros. movies have trouble remaining faithful to the Nancy Drew character and tradition, they somehow remain inordinately entertaining features, especially considering the level of filmmaking involved. Let’s take a closer look.