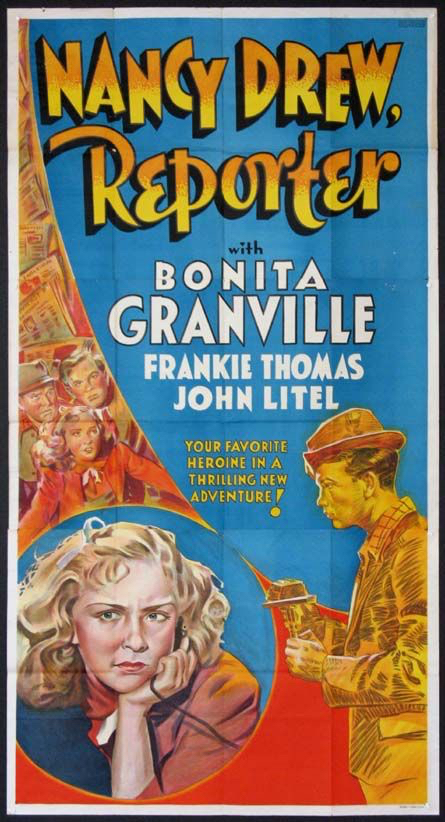

The weakest series entry is the second one, Nancy Drew . . . Reporter (1939), with an ellipsis instead of dashes in the title. Why the change? As Geoffrey Rush might say, it’s a mystery. However, the third films also uses an ellipsis, so it seems the first, with its title dashes, is the aberration.

One of six students trying to win an assignment to write for the city paper, Nancy skips her assigned human interest feature to go after a murder story in which a woman was poisoned. As she tracks a suspicious character with a cauliflower ear (Jack Perry), Nancy and Ted are joined by Ted’s bratty sister Mary (Mary Lee) and her friend Killer Perkins (Dickie Jones), a pair of bored kids more interested in setting off whistle bombs and generally interfering than helping Nancy save an innocent woman accused of the crime.

This movie has two memorable sequences: the gym scene where Ted is forced to spar against the pro boxer with the cauliflower ear, and the Chinese restaurant scene where the kids are forced to sing for their suppers (as they have no cash). Such singing scenes were staples of that era’s movies, but as good as the kids are singing a jazzy melody combining various kids’ songs and nursery rhymes, it’s the type of scene that seems utterly out of place today. Interestingly, it is the only such sequence in the four films; even then it must have seemed awkward and forced.

This film is also the weakest in terms of mystery; there is little doubt as to the killers’ identities. The script also has some nagging inconsistencies, such as the boxer not recognizing Nancy at the gym even though they’ve already had a face-to-face confrontation. Nancy even goes as far as planting a phony news story in the paper, which fair-minded Nancy would never do.

Even with these flaws, however, the film is not a total waste. It is true that Nancy’s friends Bess and George are nowhere to be found in this, or any of the Warner Bros. films. But one relationship which is transferred to celluloid quite nicely is that of Nancy and her father, noted attorney Carson Drew. As portrayed by John Litel, a familiar face throughout 1930s and ’40s cinema, Carson is a successful lawyer who always makes time for his daughter. He is very protective of her, scolds her for her sleuthing but still allows her the freedom to make her own choices and arrives with the police to rescue her in the nick of time.